Justin popping back in. Today, the NYT issued a correction to its story on Mamdani’s impact on the NYC primary electorate, and what I described yesterday as a “staggering” departure from the norm:

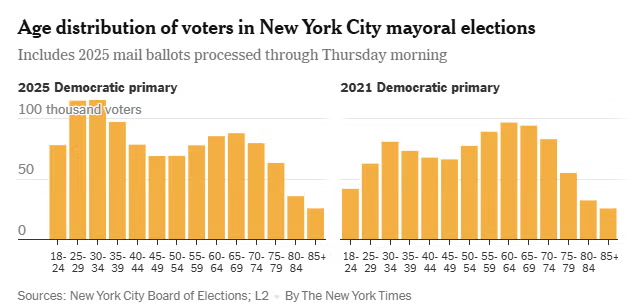

A correction was made on June 30, 2025: An earlier version of the chart in this article showing voters by age incorrectly identified the age group with the largest turnout. It was voters aged 30 to 34, not those aged 18 to 24.

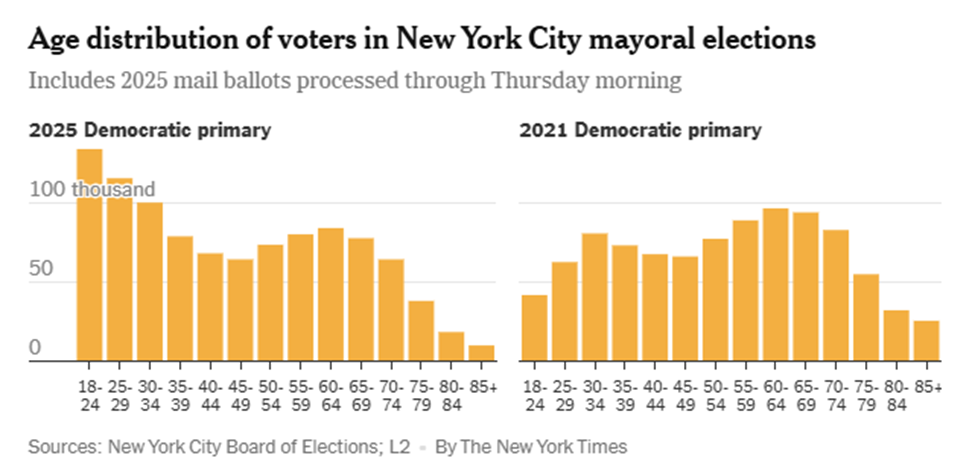

Here’s the original chart:

And here’s the update:

To be clear, that turnout by younger voters (both 18-24 and 25-29 year-olds) is still eye-popping, both as a primary-over-primary increase and as an absolute. The 18-24 turnout is just a little less “staggering” than it looked yesterday.