Gerald Seib in the Wall Street Journal with an extensive analysis on both the recent history and current polarized climate that sets the stage for the prospect that a third-party campaign could roil the 2024 presidential election:

“A Pew analysis of congressional voting last year illustrated the trend. It found that, on average, Democrats and Republicans in Congress are farther apart ideologically now than at any time in the past 50 years. Today there are only about two dozen lawmakers who could be identified as “moderate,” compared with more than 160 a half a century ago. An analysis of congressional votes showed that both parties have moved away from the center, though Republicans have moved significantly farther to the right than Democrats have to the left.

“The balance of power between the two parties actually seems to be exacerbating the trend. The political system appears trapped in an endless loop of frustration, in which control bounces back and forth between Republicans and Democrats and neither can break out to implement a clear agenda. Each of the last five biennial elections has been a “change election,” in which control of at least one branch of the national government—the House, Senate or White House—has changed hands. Meanwhile, the anger stoked on social media alienates many Americans and drives them to the extremes of the ideological spectrum.

“It might seem that this balance of power would prompt the two parties to work together in the center, but it has had the opposite effect: With little to no margin for error, leaders of both parties seem desperate to hang onto their most reliable, ideologically motivated base voters, and afraid to take the chance of offending those base voters by compromising too much with the other side. …

“No Labels leaders insist that they see not just a chance to run but to win, based on polling the organization has done nationally and, in recent days, in eight presidential battleground states. Dritan Nesho, the group’s pollster, says that battleground-state polling found that between 60% and 70% of voters in swing states said they would be open to considering a moderate, independent presidential ticket if the main-party choice is between Joe Biden and Donald Trump, similar to the sentiment found nationally. ‘Our models suggest that if we were able to convert about six in 10 of these voters we would win the Electoral College outright with 286 Electoral College votes,’ he says.” …

The group’s leaders say they won’t necessarily field a ticket if they don’t see a chance for victory—or if their efforts seem to be succeeding in moving the major parties toward the middle. ‘If they force one or both parties more towards the center of the country, if they force the political system to, for a change, actually speak to the needs of the common-sense majority instead of the wants of their bases, and that closes off an opening for a No Labels ticket, that’s fine with us,’ says Ryan Clancy, the group’s chief strategist. ‘That is success.’ The group’s leaders also say they have no interest in being a Trojan Horse that helps Trump win.”

“… the winner-take-all nature of the presidential election system, under which no Electoral College votes are rewarded for just coming close to winning a state, makes the task even harder.”

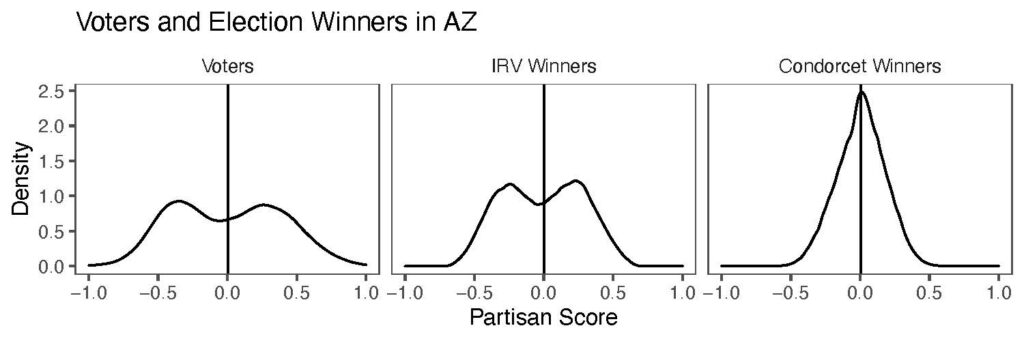

I have made it clear in numerous previous ELB blog posts why a third-party presidential bid is so dangerous unless and until states adopt ranked-choice voting, or another majority-winner system, for awarding their electoral votes.