I’m very excited to be working on this major project, bringing together my many strands of research on democracy and election law. Here’s the Publisher’s Marketplace announcement (the book itself won’t be published until early 2028):

The following is a guest post from Sandy Gordon (NYU Politics), Doug Spencer (Colorado Law), and Sidak Yntiso (Rochester Poli Sci), discussing their newly published article — “What is the Harm in (Partisan) Gerrymandering? Collective vs. Dyadic Accounts of Representational Disparities” — in the (peer-reviewed) Journal of Legal Analysis.

As Texas, Missouri, and (likely) California plunge the country back into the latest round of redistricting wars, the overwhelming majority of coverage and commentary has focused on the collective consequences of re-gerrymandering: how will these maneuvers affect majority control of the House of Representatives come 2027, and how do they affect the relationship between the partisan makeup of the states in question and the partisan composition of their respective delegations to Congress?

In a deeply polarized country with highly nationalized politics, the focus on collective consequences is understandable. And yet lost in the discussion is the impact of these maneuvers on the “dyadic” relationship between individual voters and their representatives. A dyadic perspective considers questions such as whether legislators share the values of their own constituents, whether they are competent, and whether they work hard for their communities. Not only are these the criteria by which many citizens judge their democracy; dyadic conceptions of representation also resonate with the geographic organization of Congress and the Constitution’s emphasis on individual, rather than collective, rights and harms.

In our new article, “What is the Harm in (Partisan) Gerrymandering? Collective vs. Dyadic Accounts of Representational Disparities,” published in the Journal of Legal Analysis, we explore a general account that centers the dyadic relationship of voters and their representatives in debates about the fairness of districting plans.

When is a Map Fair to Voters?

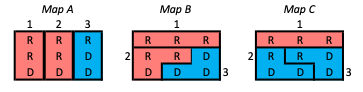

To capture the intuition, consider an imaginary state composed of nine voters—five Republicans and four Democrats—evenly divided among three districts. Three maps are proposed: A, B, and C. In Map A, Republicans have a 2–1 majority in Districts 1 and 2 and Democrats have a 1–2 majority in District 3. In Map B, Republicans have a 3–0 majority in District 1 and a 2–1 majority in District 2, while Democrats enjoy a 0–3 majority in District 3. In Map C, Republicans have a 3–0 majority in District 1, and Democrats a 1–2 majority in Districts 2 and 3.

Focus for the moment on a comparison between Maps A and B. Which is more fair? If all that matters is how closely the partisan breakdown of the elected assembly matches that of the electorate, there’s no meaningful difference between the two partitions: Both may be expected to generate a delegation consisting of one Democratic and two Republican legislators. And with nine voters and three legislators, this is as close as you can get to proportionality—one possible criterion for collective fairness.

From a dyadic perspective, however, the maps are not the same—but why they differ depends on what voters ultimately care about. In Map A, six out of nine voters have a representative from their own party, while in Map B, eight out of nine do. So, if voters only care about having a representative who shares their values, Map B is a clear winner. But suppose voters are apprehensive of lopsided majorities—perhaps because these encourage shirking by incumbent legislators. In that case, Map A might be preferable.

Now look at Map C: no matter what collective or dyadic criterion you employ, this third map is unfair.

Our paper generalizes the intuition from these examples by presenting a stylized formal model that grounds the welfare of voters in terms of (a) the correspondence between their values and those of their legislator (as captured by co-partisanship); (b) legislator competence; and (c) legislator incentives to work hard on behalf of their constituents.

The model yields measures of “representational disparity” that capture how fairly different groups of voters (e.g., Republicans and Democrats) are treated under a given map. As with collective metrics such as the efficiency gap and partisan bias, the measure can be tested across ensembles of millions of alternative maps, revealing whether an enacted plan is a true outlier or simply reflects the geographic distribution of a state’s voters.

Critically, these measures can be “tuned” to reflect features of the underlying political environment and the user’s commitment to different, potentially contradictory values. For example, if matching legislator and constituent partisanship is the overriding concern, then a map that makes districts maximally non-competitive might come closest to achieving that objective. But if motivating legislators to work hard on behalf of a broad range of constituents matters, then the measure will reward more competitive plans.

What the Evidence Shows

Relationship to existing measures. While our approach forges new conceptual ground, our measures will generally be correlated, though imperfectly so, with existing measures like partisan bias, efficiency gap, and declination. But situations may arise where our dyadic commitments lead to different substantive conclusions than collective ones would.

Examples from the paper. Using examples from a handful of states, our article shows that traditional metrics often miss the mark. For instance, in Massachusetts, Republicans rarely win congressional seats—not necessarily because of gerrymandering, but because their voters are too evenly spread out. Dyadic analysis reveals more nuanced harms: while all maps disadvantage Republicans collectively, some alternatives give them better representation at the district level. By contrast, in Florida and Pennsylvania, enacted maps emerge as extreme outliers under both collective and dyadic metrics, making the case for unfairness much clearer.

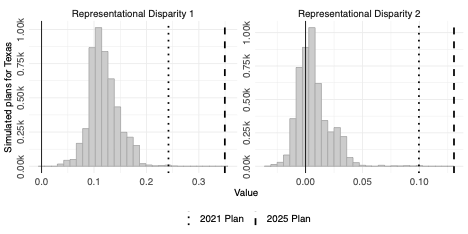

Analyzing the 2025 Texas and California Maps. Using the approach described in our article, we conducted an outlier analysis to assess the extremity of the enacted Texas and proposed California maps on dyadic representational grounds under two different “tunings” of representational disparity. Here’s a comparison of the 2021 and 2025 Texas maps with an ALARM ensemble of simulated maps. (In all graphs, the solid vertical line indicates zero disparity.)

As the figures indicate, the 2021 Texas map was already an extreme outlier irrespective of how the measure is tuned. The new map is even more extreme.

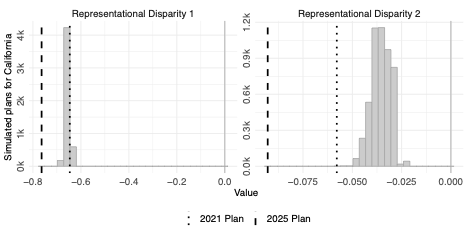

Here’s our analysis of California:

Our analysis suggests that according to the first version of the measure, which prioritizes matching constituent and legislator partisanship, the 2021 California map is not an outlier, but the 2025 proposed map would be. According to the second version, which rewards competitiveness, both maps are extreme outliers, but the 2025 plan would be worse.

Why This Matters

It is certainly not clear (to us) that single-member districts are the most effective way to select our representatives. Yet it is the system we have, and a system of representation inescapably rooted in geographic districts must be evaluated using diagnostics that treat districts and their boundaries not merely as an inconvenience but as an intrinsic feature. Gerrymandering isn’t just about partisan balance sheets—it’s also about whether citizens can trust that their voices are heard in the halls of power.

A panel of the Court of Appeals for the First Circuit affirmed a district court’s preliminary injunction against a Maine ballot initiative that prohibited “foreign governments and ‘foreign government-influenced entit[ies] from contributing or otherwise influencing candidate elections and ballot initiatives.” The district court granted the plaintiffs’ preliminary injunction motion on the ground that a substantial application of the statute was unconstitutional and that plaintiffs were likely to succeed on the merits. In a 47-page opinion, Judge Lara Montecalvo upheld the lower court’s decision.

According to the Court:

The Act states that “[a] foreign government-influenced entity may not make, directly or indirectly, a contribution, expenditure, independent expenditure, electioneering communication or any other donation or disbursement of funds to influence the nomination or election of a candidate or the initiation or approval of a referendum.” Tit. 21-A, § 1064(2).

The district court upheld the Act’s ban on political spending by foreign corporations. But the court concluded that a substantial number of the Act’s application was likely unconstitutional. From the opinion:

In the end, because the district court determined that a substantial number of the Act’s applications likely violated the First Amendment, and the remaining factors favored a preliminary injunction, it enjoined the Act in its entirety. Id. at 55-56. In doing so, the district court expressly noted Maine severability law but declined to sever given the expedited and preliminary nature of the proceeding; instead, the court reserved the issue for later consideration. Id. at 55.

Maine timely appealed, arguing that the district court abused its discretion as to its holdings regarding preemption, the applicable level of scrutiny, the state’s compelling interest, and whether the Act was narrowly tailored. Maine also argued that the Act was not facially invalid, the injunction was overly broad, and the district court abused its discretion in reserving its decision on severability. Since March 21, 2024, the proceedings have been stayed pending appeal.

This case raises a number of interesting issues including the level of scrutiny applicable to political spending by foreign citizens and whether one can distinguish the speech of a domestic subsidiary from the speech of its foreign parent company.

NPR on the push for state voting rights acts.

A great new piece from Bolts on the mechanics of LA’s attempt to serve eligible voters experiencing homelessness.

I have written this draft, forthcoming this spring in Volume 134 of the Yale Law Journal. I consider it my most important law review article (or at least the most important that I’ve written in some time). It offers a 30,000-foot view of the state of election law doctrine, politics, and theory. The piece is still in progress, so comments are welcome. Here is the abstract:

American election law is in something of a funk. This Feature explains why, what it means, and how to move forward.

Part I of this Feature describes election law’s stagnation. After a few decades of protecting voting rights, courts (and especially the Supreme Court), acting along ideological—and now partisan—lines, have pulled back on voter protections in most areas of election law and deprived other actors including Congress, election administrators, and state courts of the ability to more fully protect voters rights. Politically, pro-voter election reform has stalled out in a polarized and gridlocked Congress, and the voting wars in the states mean that ease of access to the ballot depends in part on where in the United States one lives. Election law scholarship too has stagnated, failing to generate meaningful theoretical advances about the key purposes of election law.

Part II considers the retrogression of election law doctrine, politics, and theory to a focus on the very basics of democracy: the requirement of fair vote counts, peaceful transitions of power, and voter access to reliable information. Courts on a bipartisan basis in the aftermath of the 2020 election rejected illegitimate attempts to overturn Joe Biden’s presidential election victory. Yet the courts’ ability to thwart attempted election subversion remains a question mark in light of the Supreme Court’s recent decisions in Trump v. Anderson and Trump v. United States. Politically, Congress came together at the end of 2022 to pass the Electoral Count Reform Act to deter future attempts to manipulate electoral college rules in order to subvert election results, but future bipartisan action to prevent retrogression seems less likely. Further, because of the collapse of local journalism and the rise of cheap speech, voters face a decreased ability to obtain reliable information to make voting decisions consistent with their interests and preferences. Meanwhile, parties have become potential paths for subversion. Party-centered election law theory and the First Amendment “marketplace of ideas” theory have not yet incorporated these emerging challenges.

Part III considers the potential to transform election law doctrine, politics, and theory in a pro-voter direction despite high current levels of polarization, the misperceived partisan consequences of pro-voter election reforms, and new, serious technological and political challenges to democratic governance. Election law alone is not up to the task of saving American democracy. But it can help counter stagnation and thwart retrogression. The first order of business must be to assure continued free and fair elections and peaceful transitions of power. But the new election law must be more ambitiously and unambiguously pro-voter. The pro-voter approach to election law is one grounded in political equality and based on four principles: all eligible voters should have the ability to easily register and vote in a fair election with the capacity for reasoned decisionmaking; each voter’s vote is entitled to equal weight; the winners of fair elections are recognized and able to take office peacefully; and political power is fairly distributed across groups in society, with particular protection for those groups who have faced historical discrimination in voting and representation.

Joshua Kleinfeld and Stephen Sachs have posted this paper, forthcoming in Notre Dame Law Reivew, on SSRN. Here’s the abstract:

Many of America’s most significant policy problems, from failing schools to the aftershocks of COVID shutdowns to national debt to climate change, share a common factor: the weak political power of children. Children are 23% of all citizens; they have distinct interests; and they already count for electoral districting. But because they lack the maturity to vote for themselves, their interests don’t count proportionally at the polls. The result is policy that observably disserves children’s interests and violates a deep principle of democratic fairness: that citizens, through voting, can make political power respond to their interests.

Yet there’s a fix. We should entrust children’s interests in the voting booth to the same people we entrust with those interests everywhere else: their parents. Voting parents should be able to cast proxy ballots on behalf of their minor children. So should the court-appointed guardians of those who can’t vote due to mental incapacity. This proposal would be pragmatically feasible, constitutionally permissible, and breathtakingly significant: perhaps no single intervention would, at a stroke, more profoundly alter the incentives of American parties and politicians. And, crucially, it would be entirely a matter of state law. Giving parents the vote is a reform that any state can adopt, both for its own elections and for its representation in Congress and the Electoral College.

The article mentions J.D. Vance’s support for the idea.

Photo ID concerns across the pond.

Unfortunately, even the changes contemplated are small – modifications in how individuals with convictions can apply for an advisory opinion on whether they’ve managed to figure out how much they owe the state in fines and fees.

The Prison Gerrymandering Project crunches the numbers, and finds that even with the delayed census data this cycle, most of the states that sought to count incarcerated individuals at their home address rather than the prison address managed to get clean addresses that did the job.

New in the Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly, from Capital’s Mark Brown: a review of recent ballot access battles in Ohio. I suspect there’s even more to add to the “major-party monopoly” argument if you add the legislature’s all-out gerrymandering war with the state Supreme Court, and the attempt to raise the threshold for citizen amendments.

Brookings with a post on the “nuanced relationship between young Latinos and the dominant parties,” in their series on younger voters.

With a very different focus on laws aimed at college voters, CNN also has a piece today on the recognition of the role that younger voters play.

The lawsuit filed today in state court by Rep. Zephyr – Montana’s first openly transgender lawmaker — and several of her constituents contends that her censure and subsequent barring from Capitol grounds violates the Montana state constitution.

I’m still hoping this isn’t a trend.

Zachary Roth on efforts targeting a younger segment of the electorate.