I’m going to catch a lot of flak for this post, so let me begin with with some positive words about Marc Elias, one of the country’s leading (and certainly one of this country’s busiest) election lawyers representing Democratic party and allied interests. And his work was indispensable and heroic in the immediate aftermath of the 2020 election when he and his team helped defeat scores of lawsuits brought by Donald Trump and his allies in Trump’s attempt to overturn the election results based upon ludicrous claims of voter fraud and election irregularities.

But Marc is a controversial figure in the election law world, and he’s become something of an online bully, castigating those who disagree with him even on issues of strategy and tactics who might be natural allies. And once Marc attacks, he has 600,000 Twitter followers who follow suit and believe (thanks in part to some of Marc’s own posts and media appearances) that Marc is singlehandedly fighting against attempts to suppress votes and subvert election outcomes. (In fact, much of this work is done by voting rights lawyers, many without any affiliation with the Democratic Party.) I get lots of messages from election lawyers and professors complaining about Marc but reluctant to voice their criticisms publicly.

As far back as 2015, some voting rights advocates expressed the view that Elias was not following good strategy in pushing an aggressive reading of the Voting Rights Act in cases going to increasingly conservative federal courts. As one advocate recounted to me: “The voting rights community is concerned that that SCOTUS will use these cases to essentially wipe out Section 2 and removing the few teeth it has left. An adverse decision in these cases would give states a blank check to pass truly harmful laws without any vehicle for opponents to challenge them.”

Marc didn’t listen to such criticism, and he brought what I considered to be an extremely weak Voting Rights Act case in Arizona to disastrous results. As I posted at SCOTUSBlog in Feb. 2021 about the upcoming Bnrnovich case, “The Democratic Party’s aggressiveness in using Section 2 in this case, and the deeply split en banc U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit decision siding with the Democrats, has provided an opportunity for the state’s Republican Party, its Republican attorney general and the Trump administration (which filed an amicus brief on behalf of the United States before Donald Trump left office) to suggest various ways to read Section 2 as applied to vote denial claims in very stingy ways.” And indeed the Supreme Court took this opportunity in Brnovich last summer to severely weaken Section 2. As I explained in this NY Times oped, in “Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee, the court has weakened the last remaining legal tool for protecting minority voters in federal courts from a new wave of legislation seeking to suppress the vote that is emanating from Republican-controlled states.”

It’s not just about voting rights. Right now, there is an opportunity for real bipartisan movement on anti-election subversion legislation, including reforming the opaque and vague Electoral Count Act. As I explained last week at Slate, “The debate over whether Democrats should pursue their large voting rights package or a narrower law aimed against election subversion became moot on Wednesday when Democrats could not muster up enough votes to tweak the filibuster rule to pass their larger package. Some Republicans are now making noise that they would support narrower anti-election subversion legislation centered on fixing an 1887 law known as the ‘Electoral Count Act.’ Democrats should pursue this goal but think more broadly about other anti-subversion provisions that could attract bipartisan support. Bipartisan, pinpointed legislation is the best chance we have of avoiding a potential stolen presidential election in 2024 or beyond.”

Even though Marc has said that he mostly agrees with me on this point, his main public position has been that anti-ECA legislation is some kind of “trap.” Matt Yglesias went hard after Marc for his public statements against ECA reform, and Marc has been relentless in his criticism of other professors who have (like me) been pushing for bipartisan reform. (When he’s angry he tends to compare professors to “pundits” or to contrast them with “real” lawyers like him who practice law full time.) There are at least half a dozen Republican Senators who are in talks about anti-election subversion legislation, and that is at least a half a dozen more than those who support the Democrats’ larger voting package (a package which apparently has no chance of passing whether there is ECA reform or not.) This is an opportunity that should not be passed up, and Marc could play a much more constructive role here in working on anti-subversion legislation that could help stop subversion efforts in the states—even if it does not give Marc everything he thinks Democrats want.

And then there is Marc’s position on money in politics. Well before Marc was litigating major voting cases he was a campaign finance lawyer, fighting against regulation on the Democratic side. It was Marc working to loosen campaign finance limits on political parties, a move that has increased the role of big money in influencing candidates through the political parties.

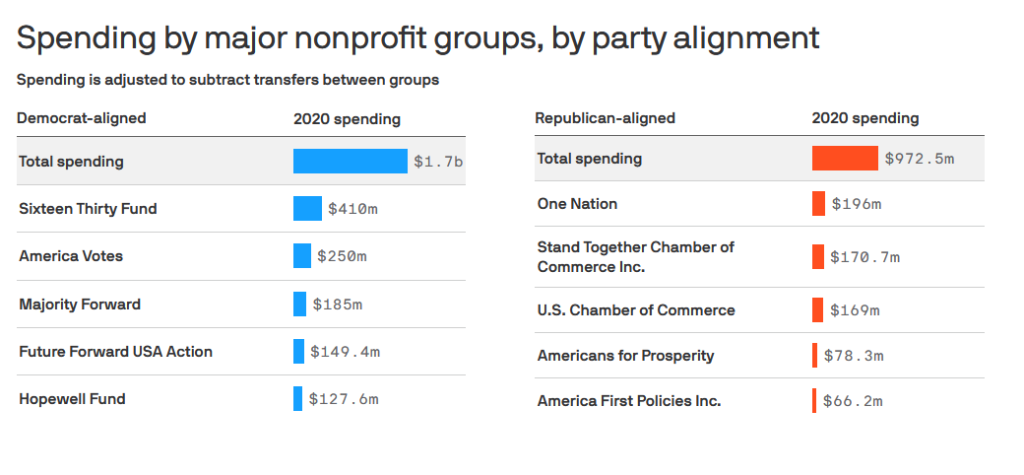

Over the weekend, the NY Times reported that Democratic non-disclosing groups have now outpaced Republican non-disclosing groups. Marc has complained that the coverage is unfair because many of the groups on the left are working on issues such as increasing voter access (as though that is a good excuse for non-disclosure of the group’s donors—it’s not). One election lawyer wrote to me, “And did you notice that Elias was paid $20 million by dark money groups to fund his rogue, scattershot legal work in 2020?” The NY Times’ Nick Confessore made a similar observation on Twitter, and he got attacked by the Elias army. Marc’s primary response to the NYT reporting on Democratic-side “dark money” is to call to make it easier to sue journalists for defamation. (He’s since deleted the tweet but this followup remains.)

And this brings me to my final point, about Marc’s style. It is fine to be zealous in one’s advocacy, but one need not be an aggressive bully on social media or elsewhere. I wish that Marc would emulate better the demeanor and manner of his Perkins Coie predecessor, Bob Bauer. No one would accuse Bob of lack of zealousness in representing his clients. But Bob seldom raised his voice, and welcomed (and continues to welcome) fair and civil debate with those with whom he disagreed.

They say you can catch more flies with honey than vinegar, and I think Marc could take a lesson in how to productively engage not just his adversaries but many who sympathize with many of his ultimate goals. And perhaps listen more to others who share overlapping goals but disagree on strategy.

Update and correction: An earlier version of this post stated that Marc worked with Senator McConnell to push through the loosening of party money provisions contained in a 2014 bill. My memory on that was faulty. I apologize for this error but stand by the remainder of this post and the larger points.

Further update: Here’s some evidence of McConnell’s support for the provision, but not his cooperation with Marc.