Great lineup for this event at the University of Wisconsin.

Category Archives: alternative voting systems

Safeguarding Democracy Project Live and Online Program October 7: “Lessons from the 2024 Elections for 2026 and Beyond: A Conversation with Nate Persily”

Tuesday, October 7, 12:15pm-1:15pm PT, Room 1337

UCLA Law and online

Register here for in-person. Lunch will be provided.

Register here for Webinar.

Richard L. Hasen, Director, Safeguarding Democracy Project, UCLA and Nate Persily, Stanford Law School

UCLA School of Law is a State Bar of California approved MCLE provider. This session is approved for 1 hour of MCLE credit.

Announcing the Safeguarding Democracy Project’s Fall Lineup of Events and Webinars, Focused on the Fairness and Integrity of the 2026 Midterms

The Risk of Federal Interference in the 2026 Midterm Elections

Tuesday, September 16, 12:15pm-1:15pm PT, Webinar

Register here.

Ben Haiman, UVA Center for Public Safety and Justice, Liz Howard, NYU Law Brennan Center for Justice, and Stephen Richer, Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation, Harvard Kennedy School

Richard L. Hasen, moderator (Director, Safeguarding Democracy Project, UCLA)

UCLA School of Law is a State Bar of California approved MCLE provider. This session is approved for 1 hour of MCLE credit.

Lessons from the 2024 Elections for 2026 and Beyond: A Conversation with Nate Persily

Tuesday, October 7, 12:15pm-1:15pm PT, Room 1337 UCLA Law and online

Register here for in-person. Lunch will be provided.

Register here for Webinar.

Richard L. Hasen, Director, Safeguarding Democracy Project, UCLA and Nate Persily, Stanford Law School

UCLA School of Law is a State Bar of California approved MCLE provider. This session is approved for 1 hour of MCLE credit.

Redistricting and Re-Redistricting Controversies and the 2026 Elections

Thursday, October 16, 12:15pm-1:15pm PT, Webinar

Register here.

Guy-Uriel Charles, Harvard Law School, Moon Duchin, Director, Data and Democracy Research Initiative, University of Chicago, Michael Li, NYU Law Brennan Center for Justice, and Nicholas Stephanopoulos, Harvard Law School.

Richard L. Hasen, moderator (Director, Safeguarding Democracy Project, UCLA)

UCLA School of Law is a State Bar of California approved MCLE provider. This session is approved for 1 hour of MCLE credit.

Media, Social Media, and the Changing Election Information Environment in 2026

Thursday, October 30, 12:15pm-1:15pm PT, Webinar

Register here.

Co-sponsored by the Institute for Technology, Law & Policy

Danielle Citron, UVA Law School, Brendan Nyhan, Dartmouth College, and Amy Wilentz, UCI Emerita

Richard L. Hasen, moderator (Director, Safeguarding Democracy Project, UCLA)

UCLA School of Law is a State Bar of California approved MCLE provider. This session is approved for 1 hour of MCLE credit.

The Supreme Court, the Voting Rights Act, and the 2026 Elections

Tuesday, November 18, 12:15pm-1:15pm, PT, Webinar

Register here.

Ellen Katz, University of Michigan Law School, Lenny Powell, Native American Rights Fund, and Deuel Ross, Legal Defense Fund

Richard L. Hasen, moderator (Director, Safeguarding Democracy Project, UCLA)

UCLA School of Law is a State Bar of California approved MCLE provider. This session is approved for 1 hour of MCLE credit.

“Mapping How Mamdani’s Ranked-Choice Strategy Beat Cuomo”

NYT takes a deep dive into NYC’s ranked-choice ballots to show how Assemblyman Zohran Mamdani beat former Governor Andrew Cuomo. Big takeaway: although voters could list up to five candidates on their ballots, 54% didn’t include Cuomo at all.

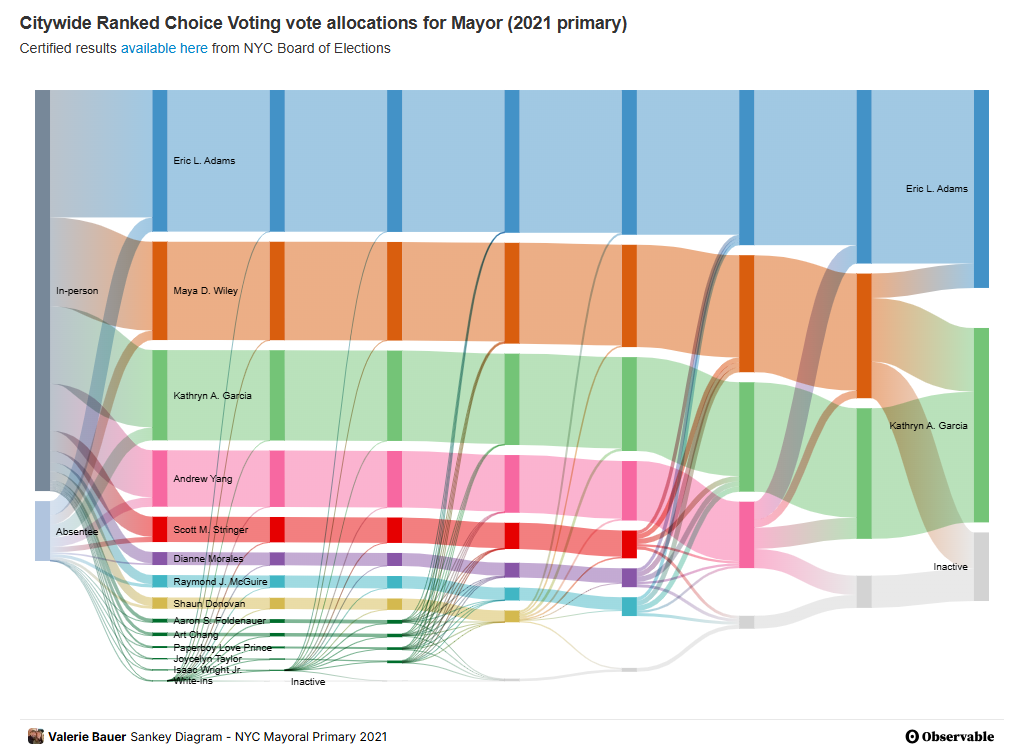

FairVote Analysis of RCV in NYC Mayoral Primary

By Rachel Hutchinson, Bryan Huang, and Deb Otis:

New York City’s third election cycle with ranked choice voting (RCV) had the second-highest turnout in city primary history. Most voters reported that they found RCV simple and wanted to keep or expand it. Now we have the cast vote record, released by the NYC Board of Elections July 24 – an anonymized digital record showing how each ballot ranked the candidates.

FairVote’s initial analysis of the results (before the cast vote record was available) can be found here. . . .

There were 20 contests with three or more candidates across 31 contested Democratic and Republican primary elections. In this blog, we will focus on the Democratic mayoral primary. The cast vote record shows that a supermajority of voters embraced ranking candidates, followed cues from candidates and campaigns, and ultimately had a greater impact on the election results.

New Podcast: “This Old Democracy”

From the Center for Ballot Freedom:

We have launched a podcast called This Old Democracy. (Political scientists often call our system “pre-modern,” meaning it’s really old, it’s falling apart in a lot of ways, and it definitely needs a serious renovation).

We have found the perfect host for the show: author and organizer Micah Sifry, who wrote Spoiling for a Fight: Third-Parties in American Politics. He will focus on the ideas, movements, and people working to renovate our faltering political system — and rebuild American democracy on a stronger, more inclusive, and truly representative foundation….

To listen, go here on Spotify or here on Apple Podcasts. Or find This Old Democracy wherever you get your podcasts.

DC Council Funds Ranked-Choice Voting

WaPo: “By a vote of 8-4, the council agreed to fund ranked-choice voting in the budget, implementing one part of Initiative 83 that voters passed last year, though they declined to fund the other portion allowing independents to vote inparty primaries.”

“New York City’s mayoral primary casts bright light on ranked choice voting — and its future nationally”

NBC reports on the big spotlight that ranked-choice voting got on Tuesday, and suggests that the election may provide both proponents and opponents with “fresh data.”

Watching NYC results unfold

My last post yesterday highlighted the patience NYC voters might need, but it looks like the verdict was pretty clear even in the first round of results, and will likely get clearer as the count rolls on.

As the count does progress, even if there’s less nail-biting over the eventual winner, you’ll want to check out the astonishingly great data visualization work of the NYC Election Atlas, brought to you by Steve Romalewski and the Center for Urban Research at the Graduate Center of CUNY. For the 2021 NYC race, they’ve got interactive maps and infographics (go to 2021 RCV results: screenshot below) showing which support came from where in which round.

More coming for 2025, and undoubtedly worth your while. (And puts the ostensibly “most detailed map of the NYC mayoral primary” to shame.)

A little bit of patience in NYC

NYC news outlets today are letting voters know they may need a little bit of patience to get results from the primary. The City’s board of elections has a helpful explainer on why. First-choice results can be tabulated right away. But if no candidate gets a majority in the first round, the last-place candidate is eliminated with redistribution of their supporters’ votes — and the city needs to know who’s in last place before doing that calculation. Which means waiting for all the ballots (including mail ballots and provisional ballots) to come in.

(UPDATE: it’d still be possible to release preliminary tentative rolling totals of both first-round and ultimate conclusion, clearly marked as preliminary, to show that the first-round total might well be misleading. And for practical purposes, the fact that there’s no “sore-loser law” in the city’s elections may mean that the primary isn’t really over until the fall.)

Also, while I’m highlighting explainers: CNN has an interactive ranked-choice primer using ice cream (perhaps to help New Yorkers beat the heat today).

And the Forward wonders whether Larry David’s to thank for the New York law that will allow people to hand out water to voters waiting on line in the heat.

“Running a low-turnout Georgia runoff election could cost $100 per vote”

The AP’s lede:

Miller County Election Supervisor Jerry Calhoun says he’s not sure anyone will vote in an upcoming Democratic primary runoff.

After all, the southwest Georgia county only recorded one vote in the June 17 Democratic primary for the state Public Service Commission among candidates Keisha Waites, Peter Hubbard and Robert Jones.

. . .

But the Democratic runoff might struggle to reach 1% turnout statewide. And counties could spend $10 million statewide to hold the election, based on a sampling of some county spending. That could be more than $100 per vote.

New York City’s ranked-choice primary

With the hotly-contested ranked choice primary in NYC on Tuesday, voters in NYC (and well beyond) are getting a lot of publicity about how ranked-choice voting works.

The New Republic offers praise for what it calls the “generally friendly, policy-focused” campaign style that the primary has engendered.

Elsewhere, Stephen Pettigrew and Dylan Radley have a column out today about errors marking the ballot, following up on their paper here. Surveying ballots from a bunch of different jurisdiction, the paper finds that 4.8% attempts to vote for an RCV office contain an improper mark, that 90% of votes with an improper mark are nevertheless ultimately counted in the final tabulation, and that the average rejection rate in ranked choice races – while small – is still considerably higher than the rate in races without ranked choice.

Both the style of campaigning and the rate of errors in marking the ballot are factors – two among many – in assessing the desirability of a system. I’ll be interested to see if the error rate in particular is at all different in the NYC primary after the considerable wave of publicity.

New Iowa law allows poll workers to challenge voters on the basis of citizenship, bans ranked choice voting, and changes major party status rules

Tom Barton for the Cedar Rapids Gazette:

House File 954 addresses elections laws regarding voter registration, citizenship and major party status. It also bans ranked choice voting in Iowa.

It adds citizenship status to age and residency under which an election precinct official can challenge someone’s voter registration, and creates new language on declaration forms confirming the voter is a U.S. citizen.

The new law allows the Iowa Secretary of State to use state and federal documentation to determine the U.S. citizenship status of Iowans on the state’s voter registration list and create a new voter registration status of “unconfirmed” for individuals whose citizenship the state cannot verify. It requires the Iowa Department of Transportation to send the Secretary of State a list of each person 17 years and older who has submitted documentation to the DOT indicating they are not a citizen.

The piece also covers the new recount law, which I wrote about here.

. . .

A political party’s candidate for governor or president will need to receive at least 2 percent of the general election vote in three consecutive election cycles as opposed to one to be recognized as major political parties in Iowa.

“An Initial Assessment of Proportional Ranked-Choice Voting in Portland, Oregon”

New report from AEI by Kevin Kosar, Jaehun Lee, and Jack Santucci:

Our core findings are as follows:

- Voter Choices. There were more candidates overall in 2024 than in past elections, although each voter could choose only among the candidates who ran in their districts. The number of candidates pursuing each council seat, however, was consistent with those in past elections and sometimes lower. Voters could better express their choices by virtue of ranking their candidate selections and being represented by more than one member. Yet the ranking of candidates had little effect on the outcomes.

- Increased Voter Turnout. Replacing a two-round election for city council with a general election in November resulted in more votes cast for city council races at the first stage of candidate elimination. But there was no clear increase in voter turnout after Portland enacted its new electoral system.

- Better Racial Representation. The candidate pool across all districts was racially diverse, with the share of black candidates greatly exceeding the share of blacks in Portland’s population, although Asians, Latinos, and whites were underrepresented in the candidate pool compared to their shares of the population. The racial composition of elected city council members was similarly diverse, with the shares of Asians, blacks, and Latinos elected reaching or exceeding the shares of these groups in the city population.

- Increased Neighborhood Representation. Dividing the city into four districts with multiple members each probably increased representation from different neighborhoods on the council, yet there are not good data to substantiate this determination.

It is too early to draw strong conclusions. Limited data availability also makes it hard to provide pre-to-post-reform comparisons in some dimensions. However, this report should be instructive as more cities consider similar changes.