Years ago in conversation with an originalist and textualist, the person I was speaking to defended originalism and textualism as constraining judges. The counterexample on the right was Justice Alito voting his values. The idea is that if all judges embraced these supposedly neutral methods of interpretation, their values would matter less, and this would be good for everyone on the left and right.

I’ve always been skeptical about these claims, and believe that in the most salient cases (the ones that make the front page of the New York Times) a justice’s values matter the most whether or not they claim they are doing originalism and textualism. (I make this argument most fully in my book on Justice Scalia’s jurisprudence, The Justice of Contradictions.)

Justice Alito didn’t start off a textualist but in more recent years, he has purported to be one. But his purported textualism never constrains his bottom line, which is relentlessly tied to his socially conservative values. I developed this argument most fully in my Senate Judiciary Committee testimony analyzing Justice Alito’s particularly poor textual analysis in Brnovich v. DNC. Justice Alito completely mangled the words of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act to create a state-friendly test that severely weakens the Voting Rights Act in the context of vote denial claims. He made a similar move in his dissent in last week’s Allen v. Milligan case.

So it should be no surprise that Justice Alito engaged in bad faith (and simply bad) textualism in his attempt in the Wall Street Journal opinion pages to prebut a Propublica report that showed that he took an unreported trip on a private plane owned by billionaire Paul Singer to go to a lodge (paid for by another person) in Alaska for a fishing trip. Propublica estimates that such a ride could cost $100,000 (though Alito said the seat would have been empty if he didn’t take it, somehow rendering the free seat valueless).

Justice Alito argues that he need not have reported the free travel on his disclosure forms under the rules as they existed because (now quoting Alito quoting the rules): “[p]ersonal hospitality need not be reported,” and “hospitality” was defined to include “hospitality extended for a non-business purpose by one, not a corporation or organization, . . . on property or facilities owned by [a] person . . .”

Now one problem with this is that it was not clear that this was “personal” hospitality. Justice Alito goes out of his way to say multiple times that he barely knew Paul Singer (despite Singer being on the trip, introducing Alito at FedSoc events, etc.) This is an argument that boxed Alito in, as Charles Geyh told Propublica:

“If you were good friends, what were you doing ruling on his case?” said Charles Geyh, an Indiana University law professor and leading expert on recusals. “And if you weren’t good friends, what were you doing accepting this?” referring to the flight on the private jet.

But the even weaker part of Justice Alito’s textualist argument is arguing that transportation (on a private jet) constitutes “hospitality on … facilities” owned by a person. Here’s what Justice Alito says about this in his WSJ piece:

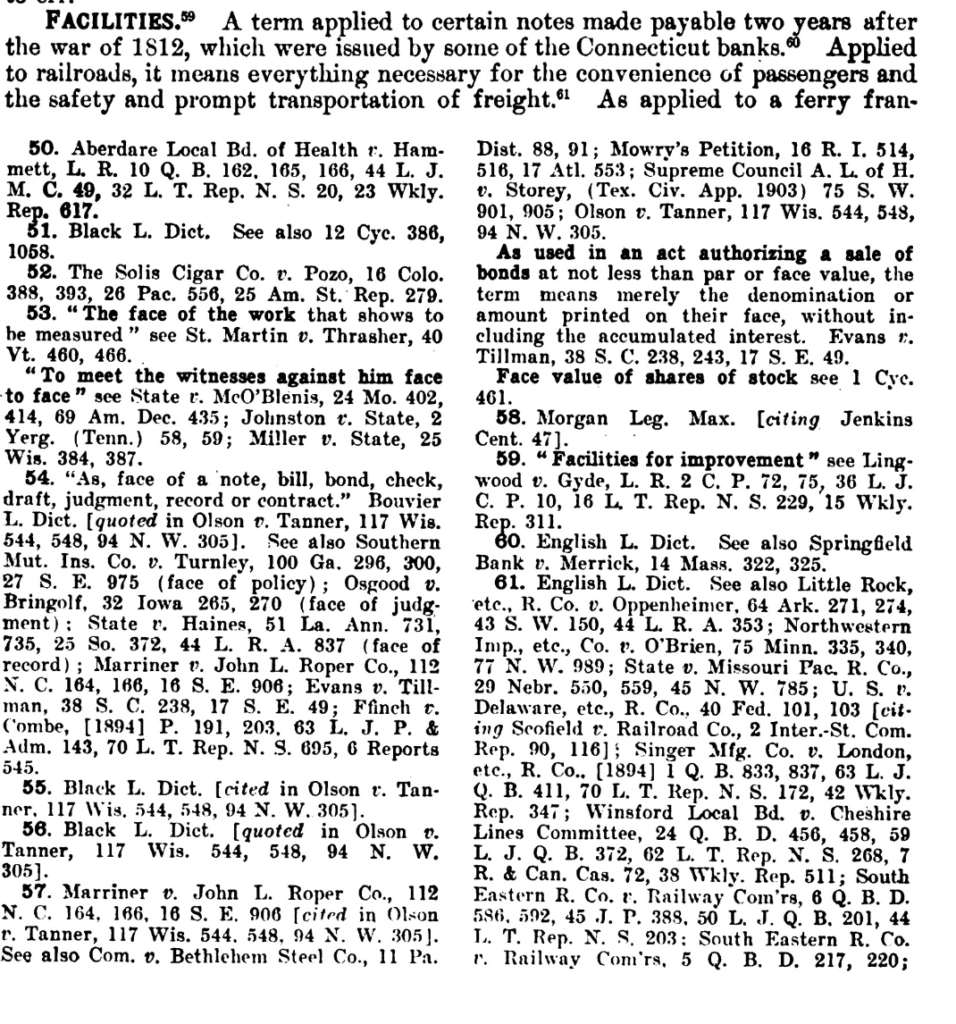

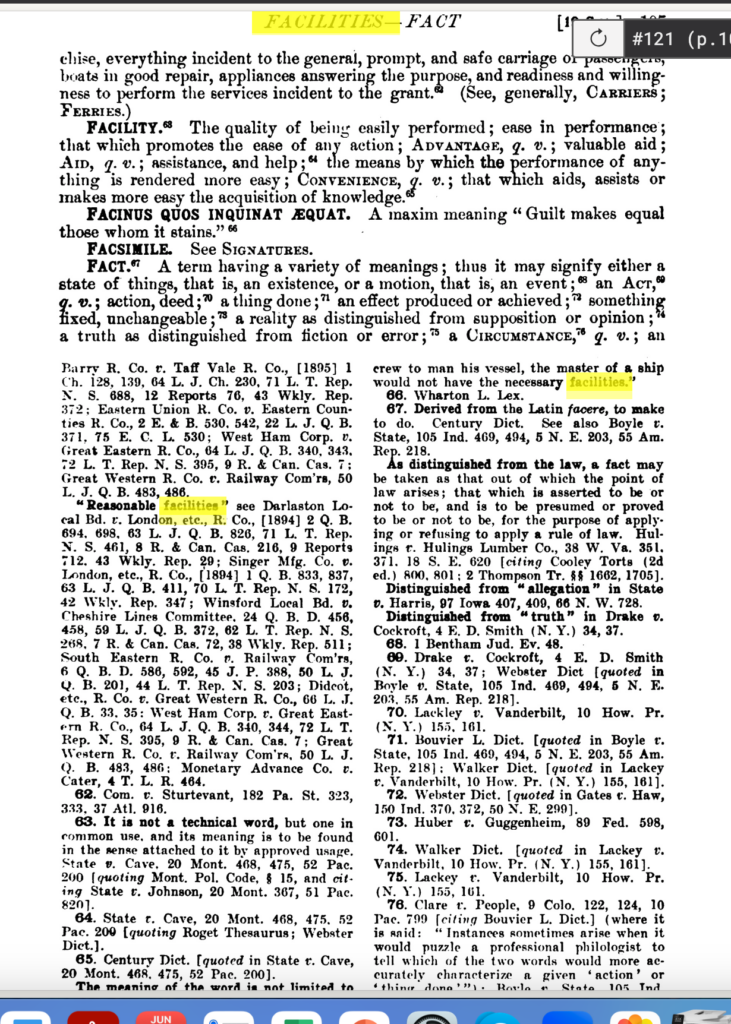

The term “facilities” was not defined, but both in ordinary and legal usage, the term encompasses means of transportation. See, e.g., Random House Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary of the English Language 690 (2001) (defining a “facility” as “something designed, built, installed, etc., to serve a specific function affording a convenience or service: transportation facilities” and “something that permits the easier performance of an action”). Legal usage is similar. Black’s Law Dictionary has explained that the term “facilities” may mean “everything necessary for the convenience of passengers.” Federal statutory law is similar. See, e.g., 18 U.S.C §1958(b) (“ ‘facility of interstate commerce’ includes means of transportation”); 18 U.S.C §2251(a) (referring to an item that has been “transported using any means or facility of interstate commerce”); Kevin F. O’Malley, Jay E. Grenig, Hon. William C. Lee, Federal Jury Practice and Instructions §54.04 (February 2023) (“the term ‘uses any facility in interstate commerce’ means employing or utilizing any method of . . . transportation between one state and another”)

This analysis is, to use a techical legal term, bullshit. The ordinary speaker of the English language would not refer to a ride on a plane as hospitality on Singer’s “facilities.” (It might apply to use of the bathroom on the plane, a different meaning of “facilities”.) Under the noscitur a socciis canon, a word is known by the company it keeps. Here, facilities appears with the term “on property or facilities,” and the ordinary reading here would be on real property owned by a person, not on a plane, boat, or car.

Justice Alito mangled the Random House definition of “facilities,” trying to bootstrap the definition’s meaning because the definition included the example of “transportation facilities.” See here:

As used in the Random House definition, an airport might be a “transportation facility,” not an airplane.

The Justice also purported to quote Black’s Law Dictionary. I searched Black’s Law Dictionary on Westlaw in many ways and I cannot find the phrase “everything necessary for the convenience of passengers.” (Update: more on the origins of this phrase in this later post.) Perhaps that phrase is in an earlier version of that dictionary but without a citation I cannot check. And those technical legal definitions of a “facility in interstate commerce” that Alito cites—those are technical uses of the word. 18 U.S.C §1958, which Justice Alito quotes, is a statute making it a federal crime to engage in murder for hire in certain circumstances!

There is no reason to believe that the reporting requirements for judges should be read in their technical sense rather than in the sense that an ordinary reader would give to the words. That’s Scalia Textualism 101. Ordinary parlance says that a free ride on a plane is not “hospitality on facilities” owned by a person.

In the end, the reporting requirement is aimed just at this: an ordinary reader would expect (and the public would want to know) if a Supreme Court Justice got a ride on a private jet paid for by a billionaire with business before the Court. Anyone who says otherwise upon reading the reporting rule is not engaged in honest textualism.

Justice Alito’s textualist prebuttal a masterstroke? More like a horrible embarrassment.

UPDATE: It is far worse than my original analysis from last night shows. Justice Alito’s reference to “facilities” was quoting from the filing instructions. The statute itself exempts only “food, lodging or entertainment received as personal hospitality of an individual….” 5 U.S.C. s 13104. A plane is not food, lodging or entertainment (though perhaps Alito slept on his flight and would claim lodging!). Kathleen Clark develops this argument here.

Further, if Singer’s corporation owned the jet, rather than Singer personally, the exception would not apply even on Justice Alito’s own terms, because the instructions exclude corporate-owned facilities.