The proposed test for partisan gerrymandering claims in Gill v. Whitford includes a discriminatory effect prong. Under the test, a district plan can be struck down only if its discriminatory effect is both large and durable. One argument against such a prong is that states cannot tell in advance—before an election—whether their maps will violate it. The Wisconsin State Legislature, for example, complains about “the indeterminacy of the district court’s partisan-effects test,” adding that “the outcome of [the test] will be uncertain enough that no claim will be too speculative to file.”

Recent developments in North Carolina show how wrong this argument is. In fact, it is quite easy to evaluate a plan’s discriminatory effect prior to an election. This assessment may preclude litigation by showing that a map is relatively neutral. Or—as in North Carolina—the analysis may support a lawsuit by indicating that a plan will severely and persistently favor one party.

The backdrop here is that North Carolina was required to redraw its state legislative maps after many of their districts were found to be racial gerrymanders. North Carolina did not use racial data to design its new plans. But it did use electoral data, in the form of “stat packs” tallying past election results for each of the new districts.

These stat packs reveal a closely divided electorate, with each party consistently winning close to half of the statewide vote. The stat packs also reveal an enormous Republican advantage in both the House and the Senate. In the House, Republican candidates are favored in 78 out of 120 districts. In the Senate, Republicans have the edge in 33 out of 50 districts. An evenly split electorate is thus expected to yield a two-thirds Republican supermajority in the Legislature.

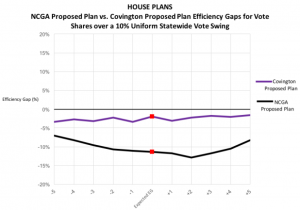

In memos published just days after the Legislature unveiled its new plans, the Campaign Legal Center examined the size and durability of their predicted efficiency gaps. The below chart plots the efficiency gaps of the House map and an alternative plan (proposed by the plaintiffs in an ongoing case) over a range of plausible electoral conditions. The House map exhibits a double-digit pro-Republican efficiency gap under most conditions, and never comes close to neutrality. In contrast, the alternative plan never diverges from neutrality by more than a couple percentage points.

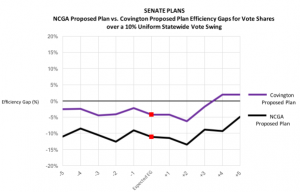

The next chart repeats this analysis for the Senate map and another alternative plan. Again, the Senate map’s efficiency gap is persistently pro-Republican, even if the electoral environment shifts by several points in either party’s direction. And again, the alternative plan’s efficiency gap is much smaller, never deviating significantly from neutrality.

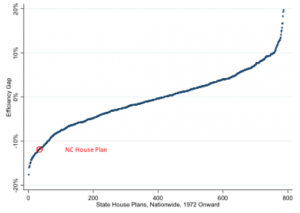

The last chart puts these figures in historical perspective. It plots the efficiency gaps of all state house plans from 1972 onward, denoting North Carolina’s new map with a red circle. The new map is plainly an outlier. In fact, its expected efficiency gap places it in roughly the worst 5% of plans in the modern redistricting era.

In combination, these studies establish that, under North Carolina’s new plans, Republicans would enjoy an advantage that is (1) very large by historical standards; (2) durable even if the electoral environment changed; and (3) unjustified given the existence of more neutral alternatives. The hollowness of the claim that a map’s discriminatory effect cannot be determined ex ante is thus exposed. We know now that North Carolina’s new plans would severely, persistently, and unjustifiably favor one party—just days after the plans were released, and more than a year before the first election under the plans.

With Whitford still pending, this information did not stop the North Carolina Legislature from passing the maps. The data nevertheless offers a glimpse of what the future might look like if the Supreme Court affirms the lower court’s decision. Plans’ discriminatory effects would be rigorously assessed as soon as they were made public. These analyses would either insulate the maps from litigation—or, as here, supply powerful evidence in support of a lawsuit.