For those following the Evenwel one person, one vote case, which the Supreme Court is hearing this week, one question is how much the Court has already settled the issue of whether a state has discretion to use total population or total (eligible or registered) voters in drawing districts. I’ve taken the view (see my latest writing on Evenwel here), that the Court strongly suggested in the 1966 Burns v. Richardson case that a state has discretion to use something other than total population, at least when the standard is not too divergent from total population. Here are the relevant sentences explaining why Hawaii’s decision not to use total population was okay:

Neither in Reynolds v. Sims nor in any other decision has this Court suggested that the States are required to include aliens, transients, short-term or temporary residents, or persons denied the vote for conviction of crime, in the apportionment base by which their legislators are distributed and against which compliance with the Equal Protection Clause is to be measured.[21] The decision to include or exclude any such group involves choices about the nature of representation with which we have been shown no constitutionally founded reason to interfere. Unless a choice is one the Constitution forbids, cf., e. g., Carrington v. Rash, 380 U. S. 89,the resulting apportionment base offends no constitutional bar, and compliance with the rule established in Reynolds v. Sims is to be measured thereby.

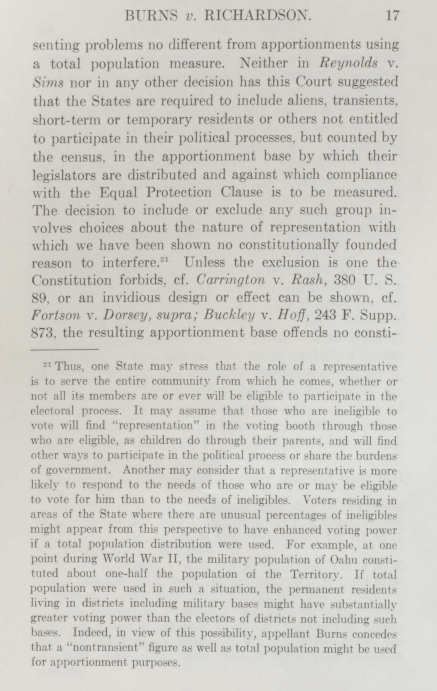

In a forthcoming article in the Harvard Journal of Law and Public Policy, Derek Muller explains that at one point the draft opinion in Burns contained a footnote right after “no constitutionally founded reason to interfere,” a footnote which disappeared by the final draft. Here’s what it looked like:

The omitted footnote gives further credence to the idea that this is the state’s choice rather than something that must be determined for all states as a matter of constitutional law. As Derek notes in his article: “This footnote would have greatly clarified the deference given to States in deciding the appropriate basis for redistricting. Perhaps it was simply because it articulated a notion of deference to the States that it was abolished—after all, the Court had been anything but deferential in the last few years in these redistricting cases, and it likely sought to reserve judgment in the future as to whether such determinations ought to be left in the hands of the States.”

Derek could well be right, and this matters a lot. As Dan Tokaji and others have argued, the big action in this case may not be whether the Supreme Court orders the use of total voters in drawing districts (that seems very unlikely) but whether the Court agrees with Texas that the states continue to have full discretion in choosing the denominator or the U.S. as amicus, which wants to enshrine total population. Dan sees the potential for political gaming if Texas wins on this point: “if the Court relies primarily on federalism, it will invite states to stop counting children, non-citizens, and other non-voters when drawing districts. Blue states will surely continue to draw districts based on total population, but we can expect red states to choose a narrower metric, one that diminishes the voting strength of minority communities and others with large non-voting populations.”

Perhaps. I think if places like Texas wanted to try this they would have tried it before under the authority of Burns v. Richardson. But the tale of the omitted footnote shows that perhaps the Supreme Court feared something just like this kind of gaming in the 1960s, and saw fit not to give states further justifications for diverging from total population [corrected].

It will be an interesting week.