The moment when the Supreme Court declined to do anything about the massive disenfranchisement of black voters throughout the South is embodied in Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes’ opinion in Giles v. Harris, 189 US 475 (1903). Justice Kagan’s dissenting opinion in the recent Voting Rights Act case, Brnovich v. DNC, which recounts the history of disenfranchisement, oddly fails to mention the Court’s own “contribution,” in Giles, to this history.

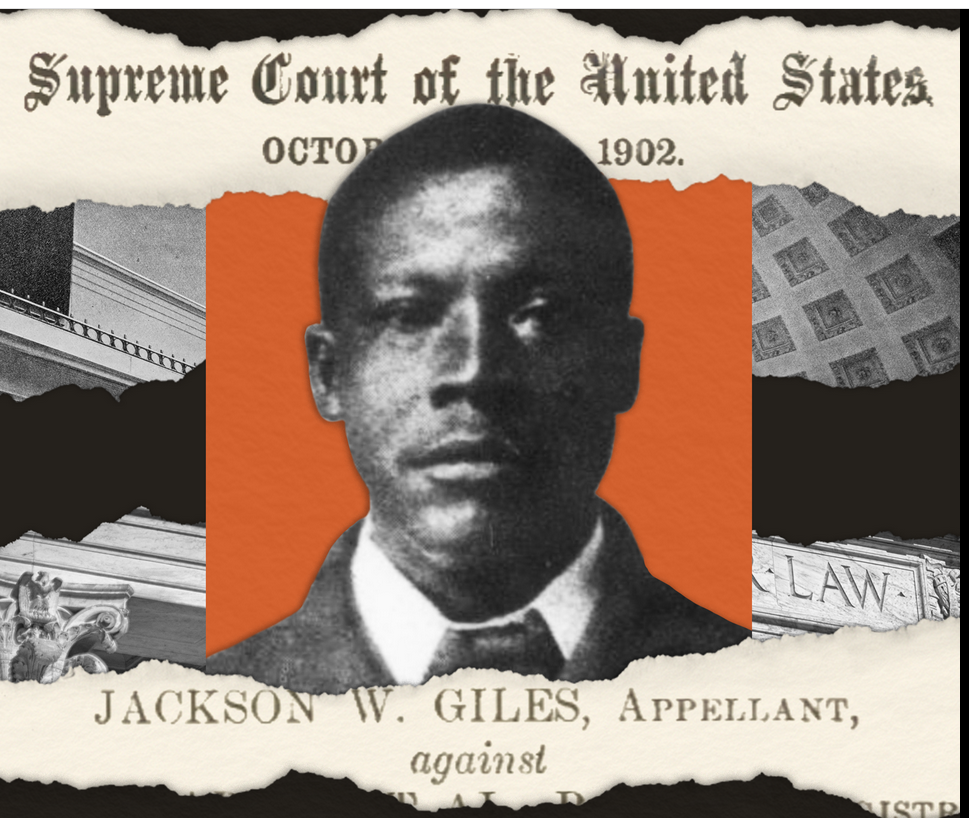

I have written about Giles, which came out of Alabama, here and here. Now comes an extensive piece of historical journalism that provides an in-depth exploration of who Jackson Giles was, as part of recovering the history of Southern black political efforts to fight back against disenfranchisement. The story contains the first photograph of Jackson Giles that I know of and I will place that dignified image at the bottom of this post.

The piece, The Journey of Jackson Giles, is written by Brian Lyman of the Montgomery Advertiser in Alabama. About the Giles case itself, the story quotes me as saying this:

“It’s my view that Giles is more important than Plessy,” said Richard Pildes, a law professor at New York University who published an influential study of the case in 2000. “Jim Crow would never have been sustainable if Black adults continued to be able to vote, or it would have been much harder to sustain it.”

About Jackson Giles himself, the feature story is incredibly rich. It’s behind a paywall, but here a couple paragraphs, after which the photo:

At the dawn of the 20th century, Dorsett’s Hall was a small island of freedom for Montgomery’s Black community amid the toxic tides of Jim Crow. The three-story building on Dexter Avenue, a few blocks away from the Alabama State Capitol, hosted dances, organizational meetings and protests. On May 5, 1903, this refuge opened its doors to Black ministers, businessmen and editors from all over Alabama.

They came to support the Colored Man’s Suffrage Association of Alabama (CMSAA) and its battle to restore their right to vote, after the passage of a new state constitution that violated the 15th amendment’s suffrage protections. Many had suffered humiliations at the hands of white registrars, like unanswerable questions or demands for letters from white men attesting to their good character. This last type of insult had spurred the leader of the CMSAA, who greeted the 150 delegates that afternoon. His name was Jackson Giles.

The 44-year-old had taken the state of Alabama all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, demanding the rights stolen from him and hundreds of thousands of Black Alabamians by the state’s Constitution, enacted 19 months before. Giles had spent a year traveling, speaking and putting together what funds he could to pay the attorney fighting the case – funds that were augmented, with or without his knowledge, by secret payments from Tuskegee Institute President Booker T. Washington.

He lost. The courts had imposed $119.80 in costs on Giles, equal to about three months’ pay. But Giles made it clear to the delegates that day that he would not surrender….

Giles was a regular face at Montgomery GOP meetings. He claimed to have attended every county GOP gathering in the 1880s and 1890s, and his colleagues sent Giles to a state Republican convention in 1884. But Giles and other Black Montgomerians also organized conferences focused on racial and labor issues, both major concerns for what was a working-class community. At one such gathering in 1888, Giles urged his fellow delegates to dig into their pockets to support the State Normal School (now Alabama State University), which had lost its state funding…

By the 1890s, Giles was an officer at most public gatherings of the Black community, often handling fundraising. His party work landed him a position as a mail carrier in 1890 – a well-paying job for the time – and in 1898, got him a position as head janitor of the local post office. Giles earned $500 a year in the role, comparable to what skilled workers of the time made. He also served as a deacon at a Congregational church. In a 1903 profile, the Colored American, a magazine published in Boston, called Jackson Giles “a highly respected citizen” of Montgomery and “a race leader of the right sort.”

In 1900, Giles was named secretary of the National Negro Race Conference in Montgomery. The conference convened to address a serious issue: the Jim Crow state constitutions that were annihilating the rights of Black Americans throughout the South. Giles and other leaders signed a “Declaration of Principles” that, among other items, demanded that “the Fifteenth Amendment of these United States stand in its original integrity.”…

Giles ran a grocery in Montgomery for a time. But he eventually gave up on Alabama. … Giles settled in nearby Taft, about 45 miles southeast of Tulsa.

Taft was one of Oklahoma’s “all-Black” towns, set up in the 1890s and 1900s in the hopes of providing safer lives for African Americans. Oklahoma was no better than Alabama for political or civil rights after 1910, but the all-Black towns offered a hope of economic independence. According to the Oklahoma Historical Society, Taft grew from 250 people in 1907 to 772 in 1940.

“We had schools and everything back then,” said Leila Foley-Davis, who grew up in Taft in the 1940s and became its mayor in 1973, the first Black woman elected as a mayor in American history. “We had five stores, we had five churches.”

Giles remarried in 1912. He acquired land, raised cotton and served as a cotton agent for a time. And Giles stayed active in politics, running for justice of the peace in 1910 and attending Republican Party conventions throughout the decade. In 1918, Giles was a delegate at a convention to create a protective association for Black Oklahomans. It took place at Tulsa’s Dreamland Theatre, which white mobs destroyed in the Tulsa Race Massacre three years later.

There is much more in the full story.