I am pleased to welcome to ELB Book Corner David Primo and Jeff Milyo, writing about their new book, Campaign Finance and American Democracy: What The Public Really Thinks and Why It Matters (U Chicago Press 2020). Here is their third of four posts:

In our first two blog posts about our new book Campaign Finance and American Democracy: What the Public Really Thinks and Why It Matters, we explained that the American public is uninformed and misinformed about campaign finance and cynical about money in politics (and politics generally)—so cynical, in fact, that there is good reason to question whether reform can have any effect on confidence in government—a key pillar of campaign finance jurisprudence. In chapter 8 of our book, we put this question to the test.

The states provide a natural laboratory for studying the effects of campaign finance reform because regulations vary across states and change over time more frequently than at the federal level. In chapter 8, we focus on trust and confidence in state government rather than the appearance of corruption, for two reasons. First, there is the matter of data availability; trust in government is a fairly standard survey instrument, so we are able to obtain dozens of national polls over a long time period that ask similar questions about this concept. Second, there is a theoretical justification. Ultimately, the courts are concerned about the appearance of corruption because of its relationship to faith in government. In Buckley v. Valeo, the US Supreme Court explicitly tied the “appearance of corruption” standard to maintaining faith in government.

We construct the largest dataset to date of survey results asking Americans about trust and confidence in state government—nearly 60,000 individual-level observations in all. Our data spans several changes in state campaign finance laws, allowing us to leverage these changes to better estimate the effects of laws, as well as the Citizens United decision, on trust, giving us a unique window into that controversial decision’s effects on trust in government.

Our book goes into detail on the underlying statistical methodology, but the bottom line is this: we find there simply is no meaningful relationship between state-level trust in government and state campaign finance laws—including contribution limits and public financing—during this time period. We view this as the most important finding in our book, as it challenges 45 years of assumptions about the role campaign finance reform plays in maintaining confidence in government.

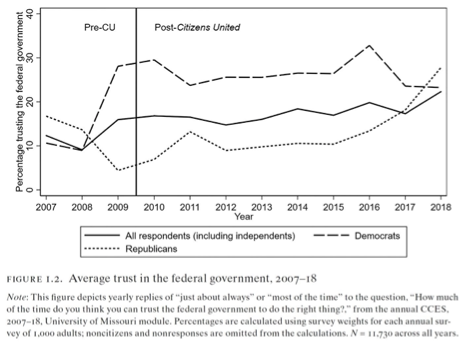

We also dispel the myth that Citizens United has destroyed Americans’ faith in government, finding no evidence that trust in state-level government was affected by the decision. Critics might argue that the null results are due to the fact that the effects of the ruling were felt nationwide, not just in states with corporate independent expenditure bans which became unconstitutional as a result of the decision. When we rerun our analysis looking at the ruling’s impact on trust in the federal government, we still find no effects. And sometimes a picture tells you as much, or more than, a regression can. Figure 1.2 of our book, reproduced below, depicts the percentage of Americans indicating that they trust the federal government to do what is right “just about always” or “most of the time.” One would be hard-pressed to look at this figure and discern any impact of Citizens United.

When we have presented these findings, we have been met with one of three reactions: This is obvious, this is wrong, or reformers don’t really mean it when they say that campaign finance reform will restore or maintain faith in government (and some critics hold all three reactions simultaneously!). In our fourth and final blog post, we will discuss the importance of our findings for the campaign finance debate.