PlanScore has been updated to include 2024 partisan fairness scores for state house and state senate plans nationwide. Also coming soon will be an aggregate evaluation of the U.S. House — both current, incorporating ongoing re-redistricting nationwide, and historical for elections from 1972 onward.

All posts by Nicholas Stephanopoulos

NY Court of Appeals Ruling in NYVRA Case

In a decision this morning, the New York Court of Appeals unanimously ruled against the town of Newburgh, the defendant in an ongoing vote dilution case under the New York Voting Rights Act (NYVRA). Newburgh argued that the NYVRA’s vote dilution provision violates the Equal Protection Clause because, to comply with the law, jurisdictions must consider race. The court declined to address Newburgh’s merits argument, holding instead that, as a municipality of New York, the town lacks the capacity to mount a facial constitutional challenge. Harvard Law School’s Election Law Clinic represents the plaintiffs, and I argued the case before the court.

This case presents the question whether the Town and Town Board of Newburgh— subordinate governmental entities created by, divisible by and even extinguishable by the State Legislature—can maintain this facial constitutional challenge to the vote dilution provision of the New York Voting Rights Act (“NYVRA”) (codified at Election Law § 17-200 et seq.). They cannot. . . .

Plaintiffs allege that (1) voting patterns in Newburgh are racially polarized and (2) the at-large election system effectively disenfranchises Black and Hispanic voters, who cannot elect candidates of their choice or influence the outcome of elections. Plaintiffs seek a declaration that Newburgh’s use of an at-large election system violates Section 17-206 and an injunction ordering Newburgh to implement either a districting plan or an alternative method of election for the 2025 Town Board election.

Newburgh moved for summary judgment on the bases that (1) Section 17-206 is facially unconstitutional because it violates the Equal Protection Clause of both the U.S. and New York Constitutions and (2) its Town Board elections comply with the NYVRA. . . .

The longstanding rule in New York is that political subdivisions—as creatures of the State that “exist[] by virtue of the exercise of the power of the State through its legislative department”—cannot sue to invalidate State legislation (City of New York v State of New York, 86 NY2d 286, 289-290 [1995] . . . .

Just as the legislature has the power to create entities to perform its functions, it has the power to change, and even destroy, those entities. Separation of powers principles accordingly demand that courts do not interfere in legislative disputes raised by legislative subordinates. Those principles are the bedrock of our federal and State Constitutions alike. . . .

Newburgh’s challenge to the NYVRA does not fall within the dilemma exception. Whatever might be said as to a municipality’s ability to bring an as-applied challenge, showing that it will be forced to take a course of action that is unconstitutional, Newburgh is pursuing a facial invalidity claim. . . . For a facial constitutional challenge, principles of “judicial restraint” (World Trade Ctr., 30 NY3d at 385) counsel strongly against permitting subordinate units of state government from using the judiciary to second-guess the wisdom of enacted legislation. A municipality’s authority to raise a challenge to a State law is at its lowest ebb when that challenge is a facial constitutional challenge, seeking to invalidate a statute in all possible applications, not merely because it allegedly placed the particular municipality in an allegedly untenable position. . . .

Newburgh’s arguments about why we should hold that it meets a dilemma exception fail to persuade us. Newburgh has not shown that compliance with the NYVRA would force it into taking an unconstitutional action. The litigation has yet to even proceed to trial, making presently unknown: (1) whether Newburgh would face any liability; and (2) in the event it did, what a court would require it to do. The NYVRA’s vote-dilution provision leaves courts wide latitude in designing remedies, so that to prevail on its facial challenge, Newburgh would have to show that “every conceivable application” of the NYVRA—i.e., every possibly remedy a trial court could order—would force it to take an unconstitutional act . . . .

Newburgh contends that because, in its view, the NYVRA violates the U.S. Constitution, the Supremacy Clause overcomes New York’s bar prohibiting its subordinate local governments from suing it. Newburgh offers no authority for that novel proposition, which would authorize every local governmental entity to sue to challenge as unconstitutional any State legislation arguably affecting that subordinate entity. . . .

Newburgh argues that “any alteration of its race-neutral, at-large election system in order to comply with the NYVRA’s vote-dilution provisions would be unconstitutional.” But that contention, as explained by counsel at oral argument (see oral argument tr at 8-12), rests on the proposition that a mere finding of liability itself would place Newburgh in the position of violating the Constitution or obeying the order of the court—when there is no order of the court compelling it to do anything. And in any event, several of the potential remedies mentioned by the NYVRA to redress a finding of vote dilution—such as longer polling hours or enhanced voter education—cannot reasonably be described as alterations of an at-large election system.

“Unilateral Election Administration”

John Martin has posted this article, which is forthcoming in the NYU Law Review and was awarded the AALS Election Law Section’s Distinguished Scholarship Award:

Election administration in the United States is fragmented. Instead of having one uniform system, each state governs elections under distinct rules and hierarchies. Yet, one feature remains consistent among the fifty systems: Each is led by a “chief election official.” Though some states rely on boards, most vest this authority in a single person—what this Article calls a “unitary chief election official.”

The unitary chief election official wields immense power. They enjoy unilateral authority to render decisions affecting voter registration, voting equipment, access to voting, ballot access, ballot measures, election counting and certification, and election official training, among other things. What is seemingly a procedural office can accordingly be used to impact substantive electoral outcomes. Because of this, subversive partisan actors have made increasing attempts over the years to co-opt the position, viewing it as a means to legally sway elections in their party’s favor.

Despite their significance, unitary chief election officials remain relatively underdiscussed in the literature. Questions remain about the precise extent of their authority, as well as what mechanisms exist to ensure that abusive officials can be held to account. This Article therefore makes a first, detailed attempt to answer these questions. To begin, the Article provides a descriptive account of the breadth of powers that the average unitary chief election official enjoys. It draws upon the election codes of eleven states to do this.

Next, the Article considers how to best construct an accountability regime that insulates the office from partisan manipulation. Through the lens of democracy theory, the Article concludes that we should deemphasize electoral accountability, as truly neutral chief election officials must answer to democratic principles rather than popular whims. Furthermore, we should treat ex-post forms of accountability, such as lawsuits, as secondary fail-safe options rather than as primary ones. On the other hand, we should channel more resources to ex-ante legal and internal modes of accountability. By reframing accountability for unitary chief election officials, this Article offers a path to shielding the office from undue partisan capture and, in turn, strengthening the democratic process.

“Give Parents the Vote” and Responses

The Notre Dame Law Review has published Steve Sachs and Josh Kleinfeld’s article advocating parents voting on behalf of their children, responses from me and from Joey Fishkin, and a reply from Sachs and Kleinfeld. Here are links to the pieces and their abstracts:

Many of America’s most significant policy problems, from failing schools to the aftershocks of COVID shutdowns to national debt to climate change, share a common factor: the weak political power of children. Children are twenty-three percent of all citizens; they have distinct interests; and they already count for electoral districting. But because they lack the maturity to vote for themselves, their interests don’t count proportionally at the polls. The result is policy that observably disserves children’s interests and violates a deep principle of democratic fairness: that citizens, through voting, can make political power respond to their interests.

Yet there’s a fix. We should entrust children’s interests in the voting booth to the same people we entrust with those interests everywhere else: their parents. Voting parents should be able to cast proxy ballots on behalf of their minor children. So should the court-appointed guardians of those who can’t vote due to mental incapacity. This proposal would be pragmatically feasible, constitutionally permissible, and breathtakingly significant: perhaps no single intervention would, at a stroke, more profoundly alter the incentives of American parties and politicians. And, crucially, it would be entirely a matter of state law. Giving parents the vote is a reform that any state can adopt, both for its own elections and for its representation in Congress and the Electoral College.

Joshua Kleinfeld and Stephen Sachs make a significant contribution to the literature on children’s disenfranchisement by describing and defending parental proxy voting: empowering parents to vote on their children’s behalf. The authors’ democratic critique of the status quo is particularly persuasive. Children’s exclusion from the franchise indeed distorts public policies by omitting children’s preferences from the set that policymakers consider. However, Kleinfeld and Sachs’s proposal wouldn’t do enough to correct this distortion. This is because contemporary parents diverge politically from their children, holding, on average, substantially more conservative views. The proxy votes that parents cast for their children would thus often conflict with the children’s actual desires. Fortunately, there’s an alternative policy that would fix more of the bias caused by disenfranchising children: young adult proxy voting. Under this approach, children’s votes would be allocated not to their parents but rather to young adults—the cohort of adults closest in age to children. Young adults, unlike parents, are highly politically similar to children. At present, for example, both young adults and children are quite liberal. So, to revise Kleinfeld and Sachs’s thesis, if we want children to be adequately represented at the polls, we should give young adults the vote.

“It Takes a Village . . . But Let the Teenagers Vote“

In their article Give Parents the Vote, Kleinfeld and Sachs argue that we ought to give parents extra votes to cast by proxy on behalf of their minor children. In this response, I argue that their proposal misconceives the nature of voting itself. Unlike a child’s personal medical or financial decisions, which we entrust to those most responsible for a child’s care, voting is a collective act by which a political community makes collective choices. Each of us is obligated to cast our vote in the way we think best for the whole community. And each voter—whether a parent or a nonparent—is morally and constitutionally entitled to an equal vote. At the same time, it is true that those under age 18 are often not especially well represented in our current system. Empirical evidence suggests that high school students are as able to vote as young adults. So rather than giving extra votes to their parents, I argue that we ought to let teenagers vote.

Shared ground—much more than we’d expected when Joseph Fishkin and Nicholas Stephanopoulos first agreed to write in response to Give Parents the Vote—is the most notable feature of our exchange.1 Fishkin and Stephanopoulos are two of the most distinguished election law scholars of our generation. They are both to the left of us politically. And our proposed reform, of letting parents vote on behalf of their minor children, is off the beaten track.

But witness the agreement. All four of us agree that the status quo is wrong as a matter of principle and of policy: children are “members of the American political community if anyone is,”2 and their lack of representation leaves our political system and policies “observably and significantly distorted.”3 All four of us agree that this distortion is serious enough to warrant changing the law. Stephanopoulos further agrees with us that parent proxy voting is clearly consistent with the Constitution and other federal law, and entirely up to the states,4 though Fishkin sees the equal protection concerns as more significant.5 That’s a lot of shared ground. What’s left to disagree about?

At the surface level, we plainly disagree about policy solutions. Rather than have parents represent their children at the polls, Stephanopoulos would create a system in which all young adults’ votes count for more based on how many unrepresented children live nearby—say, in the same census block group.6 (For example, in an average district, Stephanopoulos would multiply the vote of every eighteen- to twenty-nine-year-old by 1.7, so that existing young-adult voters “cover” the children under eighteen.7) Fishkin would lower the voting age to fourteen but make no further provision for those thirteen years of age or younger.8

Beneath these policy disagreements lie deep disagreements of principle, both about the purpose of voting and about the nature of the parent-child relationship. In our view, the chief point of universal suffrage is to protect citizens’ interests—what’s good for them, both materially and morally—as those citizens see their interests. Politics is about tradeoffs, and politicians are buffeted on all sides by demands for different policies. The hard lesson of experience is that there’s no way to secure equal consideration of all citizens’ interests while counting only some of their votes. Children are citizens too, and leaving this quarter of the citizenry without the vote means leaving their interests uncounted when it matters most.9 Yet since children can’t vote competently to protect their interests, their proper political representatives are their parents—to whom it falls not only to protect their children’s interests, but very often to define those interests, even when parents and children disagree.

Utah Court Ruling on Partisan Fairness Metrics

In its decision rejecting the legislature’s new congressional map, the Utah trial court included a lengthy discussion of quantitative measures of partisan fairness in districting. The legislature argued that partisan asymmetry and the mean-median difference should be used to assess its new map. The court responded, correctly in my view, that these are exactly the wrong metrics to use in Utah. These metrics are inapplicable in uncompetitive states like Utah, while other approaches, like the efficiency gap and ensemble analysis, do work in Utah’s political environment. The court’s decision is here.

The Court finds that the partisan bias test is unsuitable for assessing whether a redistricting plan in Utah purposefully or unduly favors or disfavors a political party. It is not among the best available measures to assess partisan favoritism in Utah.

First, because partisan bias assesses favoritism based solely on seat shares under a hypothetical 50-50 statewide election, scholars warn that it should not be applied in states like Utah where statewide elections are uncompetitive and a tied statewide election cannot plausibly be expected. The authors of the metric, Professors Andrew Gelman and Gary King, limited its application to “competitive electoral systems,” which they defined as states in which each party had won a majority of seats or votes in at least one election during the preceding two decades. Professor Gary King has since emphasized that partisan bias “is only appropriate for competitive situations where there is a potential for change in partisan outcomes (majority control, in particular).”

The Court finds that Utah’s statewide elections are highly uncompetitive. Democrats have not received a majority of the statewide vote in congressional elections in 35 years and have not won a majority of congressional seats since at least 1970. Republicans have also won every statewide election for president, governor, and other offices included in S.B. 1011’s partisan index during the last 25 years, nearly always with 20-plus margins. Utah’s highly uncompetitive environment also undermines the validity of the partisan bias test’s uniform shift assumption—that is, the assumption that the shift to a 50-50 statewide vote share would occur uniformly across districts. Since this scenario has not even remotely occurred in decades, it is at best unclear how electoral coalitions would shift to produce a 50-50 statewide election and whether the uniform shift assumption underlying the partisan bias test is satisfied in Utah. Thus, Utah does not satisfy the electoral conditions necessary for valid application of the partisan bias test.

Second, when applied in Utah to congressional plans, the partisan bias test yields paradoxical results that advantage Republicans and disadvantage Democrats. The test treats most 3-1 maps that include one Democratic-leaning district as biased in favor of Republicans and against Democrats, because in a hypothetical tied statewide election Democrats would not win two seats. At the same time, it treats 4-0 maps that guarantee Republicans all four seats as neutral. This irrational result stems from the test’s conflict with Utah’s political geography. To pass, a map must disperse Democrats across two districts to ensure they would win two seats in the hypothetical world of a tied statewide election. But because Democrats are a small, geographically concentrated minority, doing so dilutes their only opportunity in the real world to win one seat. . . .

Scholars have recognized this effect as the “Utah paradox”—one that is known to be gameable and the reason why partisan actors in Utah would opt to use partisan bias as their metric to assess congressional plans. Notably, the Legislature applied the partisan bias test only to congressional plans. Utah Code § 20A-19-103(1)(c), (g). The Legislature did not apply the partisan bias test to its own legislative maps or the state school board maps, all of which would fail the test for exhibiting pro-Republican bias. . . .

Unlike the partisan bias and mean-median difference tests—which yield wholly incoherent results in uncompetitive states—the efficiency gap is not inapplicable in a state as uncompetitive as Utah. As Dr. Warshaw explains, the original authors of the efficiency gap acknowledged that the efficiency gap may be inapplicable in states where one party consistently wins more than 75% of the vote, “[b]ut Utah does not fall into that category. So . . . Utah is not outside of the boundary conditions of the efficiency gap.”

The Court finds that, despite its drawbacks, the efficiency gap is an appropriate symmetry measure to consider in assessing congressional maps in Utah. It correctly identifies the party favored under a proposed congressional map and permits analysis of the extent to which that party is favored via comparison with historical congressional plans in other states. The efficiency gap is thus among the best symmetry measures available to evaluate partisan favoritism in Utah congressional maps and should be considered alongside other appropriate measures.

“Mark Cuban Joins Legal Fight Against Dark Money and Super PACs”

This is a story in Sportico about HLS’s Election Law Clinic’s amicus brief on behalf of a group of billionaires arguing that Maine’s limit on Super PAC contributions doesn’t burden their speech and serves important goals including preventing corruption and avoiding the distortion of the political system.

Dallas Mavericks minority owner Mark Cuban has teamed up with four other billionaires—hedge fund manager William von Mueffling, LinkedIn co-founder Reid Hoffman, and venture capitalists Steve Jurvetson and Vin Ryan—to argue in an amicus brief that their enormous wealth shouldn’t provide them more political influence than other Americans and that a Maine campaign finance law limiting contributions to super political action committees (super PACs) is both sensible and constitutional.

“Because of their wealth,” the brief says of the billionaires, “amici have the capacity to be extraordinarily influential in America’s political system. But amici didn’t ask for this power. And they don’t want it.”

The brief concerns Dinner Table Action & For Our Future v. William J. Schneider et al., a case brought by two Maine super PACs that accept contributions exceeding Maine’s limit. Several Maine officials, including Maine Commission on Governmental Ethics and Election Practices chairman William J. Schneider, are the defendants.

The case centers on whether a citizen referendum, overwhelmingly approved by Maine voters last year, complies with First Amendment political speech protections. The resulting act sets a $5,000 limit for super PACs. It also includes disclosure requirements regarding the identity of donors and donations related to funding communications that advocate for the election or defeat of a particular candidate. The referendum was backed by Equal Citizens and its founder, Harvard Law School professor Lawrence Lessig. . . .

Last Thursday, professors Samuel Jacob Davis and Ruth Greenwood of the Election Law Clinic at Harvard Law School submitted an amicus brief on behalf of Cuban and his colleagues. . . .

Cuban’s group sees Maine’s law as “reasonable” and “necessary to protect” democracy from “the kind of corruption that plagues too many elections.” That is especially important in a sparsely populated state like Maine, where “a relatively small amount of outside money can play an outsized role in local races that should be focused on local issues.”

The brief contends that regulating super PAC contributions imposes minimal constraints on free speech rights. It asserts that super PACs “give voters little useful information and often express a muddled political message,” with donations “often funneled through shell entities” known as “dark money organizations.” . . .

Further, the brief warns that unlimited super PAC contributions “create a serious risk of actual quid pro quo corruption and its appearance.” It cites former U.S. Senator—and now convicted felon—Bob Menendez (D-N.J.), who was accused of using super PAC contributions as payoffs for influencing a Medicare billing dispute involving a friend. The brief also points out that super PAC contributors have been appointed to high-ranking positions. For instance, current U.S. Secretary of Education Linda McMahon “had no teaching experience prior to her appointment, but she had donated tens of millions of dollars to various super PACs supporting the president who appointed her.”

More Concerns About the SG’s Proposal in Callais

I’ve already discussed a number of problems with the SG’s proposal in Callais (that plaintiffs’ demonstrative maps be required to achieve jurisdictions’ political objectives). Upon further reflection, I have two further concerns. One is that the proposal is inconsistent with the basic purpose of the first Gingles precondition. The other is that the proposal might end almost all vote dilution litigation (not “merely” suits where racial and partisan polarization coincide).

1. In Gingles and subsequent cases, the Supreme Court has been clear about the point of the first Gingles precondition. It’s to ensure that a lawful (and otherwise reasonable) remedial district could be drawn in which minority voters would be able to elect their preferred candidates. As the Court put it in Gingles, this requirement confirms that “minority voters possess the potential to elect representatives in the absence of the challenged structure or practice.” Or per Growe v. Emison, the first Gingles precondition “establish[es] that the minority has the potential to elect a representative of its own choice in some single-member district.”

Under this conception of the requirement, a demonstrative district must generally satisfy state and federal legal criteria. After all, any remedy for vote dilution must, at least, be lawful. The Court has also said that a demonstrative district must reasonably comply with traditional criteria (even ones not prescribed by state law). This rule lowers the risk of racial gerrymandering (which is usually absent when a district abides by traditional criteria). The rule also guarantees that any remedial district is not just lawful but “reasonable” in appearance as well.

The SG’s proposal, however, conflicts with the function of the first Gingles precondition. This is because the achievement of a jurisdiction’s political objectives is unnecessary for a district to be a lawful, reasonable remedy. Consider a demonstrative district that satisfies state and federal laws, complies with traditional criteria, but (against a jurisdiction’s wishes) changes the party that would likely win the seat. This district is a perfectly valid remedy for vote dilution. If adopted, it would improve the representation of the plaintiffs’ racial or ethnic group without violating any law or norm. Yet, under the SG’s proposal, the district would flunk the first Gingles precondition. Because it would change the partisan balance of the jurisdiction’s map, the district would be disallowed.

The SG’s proposal leads to this anomalous outcome—one at odds with the first Gingles precondition’s remedial orientation—because the proposal doesn’t have a remedial basis. Rather, as I’ve discussed previously, its very different aim is to ferret out intentional racial discrimination more effectively. For that purpose, incorporating a jurisdiction’s political objectives makes sense. If an additional majority-minority district could be drawn while complying with all applicable laws, norms, and political preferences, then it’s a reasonable inference that if the district wasn’t drawn, the failure to create it was racially motivated.

While this logic is sound enough, though, it has nothing to do with the remedial rationale for the first Gingles precondition. To the contrary, this is the logic of Alexander’s alternative-map requirement in the racial gerrymandering context. In that domain, the crucial question is one of intent: Did race or something else (like politics) predominate in the design of a district? To answer that question, the SG’s proposal is sensible—indeed, it recapitulates Alexander’s holding last year. With respect to racial vote dilution claims, however, the proposal is entirely inapt. It would transform an inquiry focused on available remedies into one probing for a primary racial motive.

2. In my earlier commentary on the SG’s proposal, I worried that it would doom most Section 2 claims in red states where minority voters tend to be Democrats and white voters tend to be Republicans. In these areas—including much of the South—the state would simply assert a political objective of maintaining its district plan’s current partisan balance. It would then be impossible for a plaintiff to satisfy the first Gingles precondition. No demonstrative map could both include an additional majority-minority district (as required by Bartlett) and preserve the plan’s partisan breakdown. Any new majority-minority district would be a Democratic district and would thereby change the plan’s partisan makeup.

I now think the SG’s proposal would have even more sweeping implications, effectively barring Section 2 claims everywhere, not just in the South. This is because the political objectives a state might invoke are hardly limited to maintaining a plan’s partisan balance. They could also include, inter alia, protecting all current incumbents, protecting certain incumbents but not others, increasing competition, decreasing it, preserving the cores of existing districts, and (in a challenge to at-large elections) keeping this electoral system over any alternative. I can’t imagine a Section 2 case in which some political goal wouldn’t be compromised by the construction of a new majority-minority district. To avoid liability under the SG’s proposal, then, all a state would have to do is announce the right goal. If it did so, a plaintiff would again be unable to both achieve this goal and draw an additional majority-minority district.

To illustrate, in the Callais oral argument, Hashim Mooppan referred to Harlem as a place where Section 2 claims would remain viable under the SG’s proposal. There, “[y]ou’ve got white Democrats, Black Democrats, and Hispanic Democrats who all live around the same area and who probably have at least sometimes different candidates of choice.” “If the State of New York was to draw a map in a way that … favors one of those racial groups, that’s the sort of situation where Section 2 could come in and say … there’s a reason to be worried.”

But this analysis implicitly assumes that maintaining a plan’s partisan balance is a state’s only possible political objective. It’s true enough that, in a heavily Democratic area like Harlem, this objective wouldn’t be undermined by a plaintiff’s demonstrative map, which would necessarily preserve the region’s all-Democratic delegation. But it wouldn’t take much creativity for New York to think of a different political goal that would be threatened by a new majority-minority district in Harlem. Maybe the new district would oust an incumbent whom New York would like to keep in office. Or maybe the new district would be too different from its predecessor, whose core New York would like to keep intact. Or maybe the new district would be too competitive (or too safe), while New York would prefer less (or more) competition. The point is that the list of plausible political aims is endless—meaning that so are the ways for states to skirt liability under the SG’s proposal.

“Can New Legal Challenge Reshape State’s Congressional Districts?”

This piece in Urban Milwaukee discusses the anti-competitive gerrymandering claim that has been filed against Wisconsin’s congressional districts (by a team of lawyers of whom some are at HLS’s Election Law Clinic). The piece nicely illustrates how much more competitive Wisconsin’s districts could be under a different district map.

[The plaintiffs] argue that anti‐competitive gerrymandering is distinct from partisan gerrymandering, which draws district lines to pack members of the disfavored party into a small number of districts, thus unfairly boosting the number of seats won by the favored party. Anti‐competitive gerrymandering is also distinct from racial gerrymandering. . . .

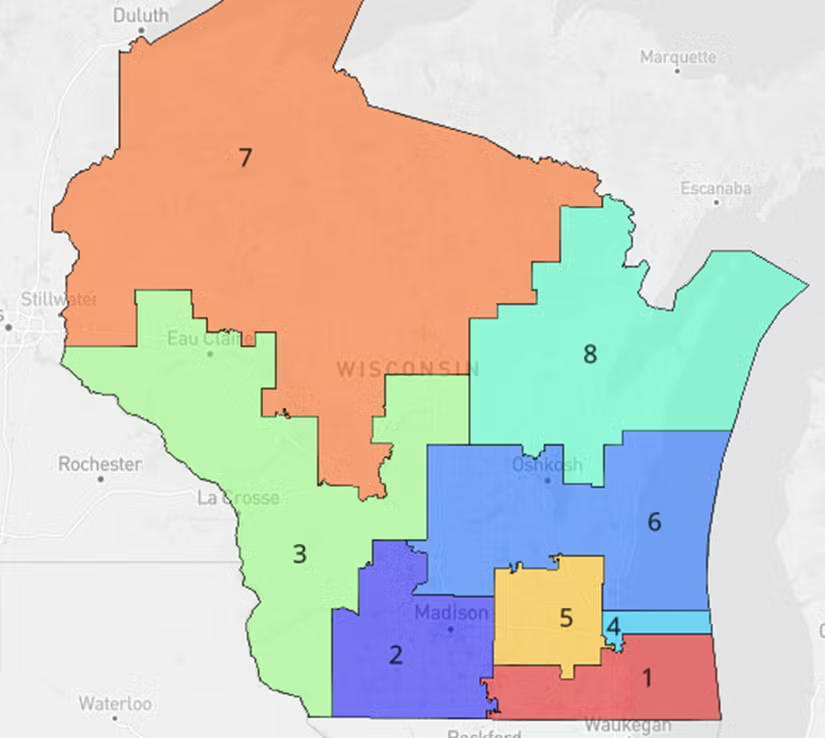

The next graph, drawn using DRA, maps today’s Congressional districts. Districts 2 and 4 are heavily Democratic, based as they are on the state’s two largest cities, Madison and Milwaukee. Districts five to eight are overwhelmingly Republican. Of the eight districts, only district one and three can be considered competitive, although both are currently Republican. . . .

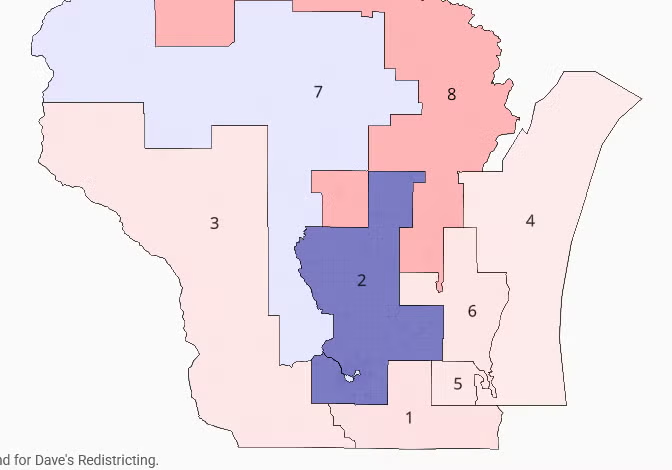

If the Wisconsin Business Leaders are successful in their challenge, what might the replacement look like? According to DRA’s analysis, the most competitive map of those submitted for Wisconsin’s congressional districts is called “muffintime’s Competitive Wisconsin.”

The next graph shows the competitiveness of each of the eight districts generated by the muffintime map. Six of the eight districts are almost perfectly competitive. In fact, none of the winners in those six districts won the majority of the votes, only a plurality when write-in votes are included.

Even in the two districts that favored one party over the other— Democrats in District 2 and Republicans in District 8—are more competitive than the six uncompetitive districts in the current map. . . .

No attempt is made here to show that the muffintime’s map was the best of all possible maps for Wisconsin’s congressional delegation. However, its obvious superiority to the current long-time map should be a sign that better and more democratic maps are possible. Competition is good for democracy.

Section 2’s Legislative History Refutes the SG’s Proposal

I’ve previously noted a number of problems with the SG’s proposal in Callais, under which demonstrative maps would have to achieve the enacted plan’s political goals in order to satisfy the first Gingles precondition. The proposal has no basis in the Supreme Court’s Section 2 jurisprudence—indeed, it would have led to the opposite outcome in cases like Milligan and LULAC. The proposal wrongly focuses on discriminatory intent rather than discriminatory effect. The proposal effectively eliminates the distinction between racial vote dilution and racial gerrymandering claims. And the proposal would allow most minority-opportunity districts in the South to be dismantled without violating Section 2.

To this (already damning) list of objections, I want to add one more, this one rooted in Section 2’s extraordinarily influential legislative history. During the Senate Subcommittee on the Constitution’s 1982 hearings on amending Section 2, arguments much like the SG’s were repeatedly aired—and repeatedly rejected. Witnesses who supported Section 2’s revision made clear that, in their view, political goals like partisan advantage or incumbent protection were not valid justifications for diluting the electoral influence of minority voters. The figures who thought those goals could excuse racial vote dilution were the opponents of the 1982 amendments, the losers of this political battle. The SG’s proposal thus amounts to gifting these critics a victory they were unable to win on the congressional floor.

Consider this exchange between former Assistant Attorney General for Civil Rights Drew Days (a proponent of the 1982 amendments) and Stephen Markman (the chief counsel of the Subcommittee on the Constitution, then chaired by Sen. Orrin Hatch, the most vocal opponent of Section 2’s revision). Markman asked Days if there was “a distinction between redistricting proposals that attempted to limit minority strength because of racial prejudice and those efforts designed to limit the strength or the impact of a particular neighborhood that might have been minority-dominated because of political or partisan identification.” Days responded: “If the intent or the effect of a practice [is] to dilute or diminish minority voting strength,” it doesn’t matter “what party they were members of. That [is] not a consideration.”

Continuing the colloquy, Markman asked about “a genuinely colorblind architect of a districting plan [who] took a look at a neighborhood and he identified it as a predominantly Democratic or a predominantly Republican neighborhood, and created district lines designed to maximize or minimize the impact of that neighborhood purely on that basis.” Days again answered: “[W]hether blacks [are] Republicans or Democrats or Socialists or whatever they may happen to be—noneuclidian Druids—I do not think that is important. What is important is, are they blacks, are they Hispanics, are they Chinese, and are they having their political power affected?”

Summing up the exchange, Markman stated: “You are … saying that this neighborhood would be immune to a gerrymander because they happen to be black?” “Yes, that is right,” replied Days. “It is one of the few immunities we have.”

In a similar vein, take Markman’s questioning of Julius Chambers (then the head of LDF and a backer of the 1982 amendments). Markman again asked if there was “a distinction between those districting plans designed to limit the influence of a predominantly minority neighborhood because of its political identification as opposed to that redistricting plan designed to limit their influence because of their race or color.” Like Days, Chambers responded that there was no difference between these plans as far as the Voting Rights Act was concerned. Unlike a partisan group, “a black group is clearly discernible. It is not difficult to [determine] that group’s representation, that is, does this particular legislation or this particular practice affect an identifiable group? Blacks are identifiable.”

Sen. Hatch himself voiced a version of Markman’s question to NYU law professor Norman Dorsen (another supporter of Section 2’s revision). “Assume … a State senate has no black members but four districts have very substantial black minorities.” Then, “[t]he legislature decides to maintain current lines for these four districts for a variety of political reasons—that is, to protect incumbents—but there is no racial motivation at all.” If “a section 2 action” were brought, would a court have to “find[] that the reapportionment plan is illegal and order[] a redistricting plan to create two districts with black majorities”? Yes, Dorsen answered, this “result would have to follow,” especially given the “history of racism” that was also part of Sen. Hatch’s hypothetical.

Beyond these exchanges, several witnesses in the 1982 hearings explained in their prepared statements that, under the amended Section 2, racial vote dilution should be cognizable even if mapmakers’ objective was political. Mississippi state senator Henry Kirksey described his state’s 1981 congressional “‘Least Change plan,” which “depriv[ed] blacks of a majority in any of the five districts.” The plan was adopted over other options that included a Black opportunity district because “adoption of one of the alternative plans would [have] jeopardize[d] the reelection chances of Mississippi’s all-white congressional delegation.” According to an advocate of the Least Change plan, “[t]o trade these [chances] for the symbolism of electing a black would throw away real political considerations.” Notwithstanding this political rationale for the Least Change plan, Kirksey argued that Section 2, as revised, should invalidate the map. “[T]hese facts should be sufficient to prove that the rights of blacks voters are violated by the 1981 plan.”

Likewise, Chambers discussed a series of North Carolina state legislative plans in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. All these plans relied on “large multi-member districts,” which “predictably led to the subversion of concentration[s] of minority citizens into the larger white population.” “The overriding motivation” for the plans, though, was not racial animus but rather “to protect the white incumbents.” Still, Chambers maintained, the amended Section 2 should reach the plans. “Amending Section 2 … will revive the private lawsuit as an effective tool for … opening up the political process [in North Carolina and nationwide] to black voters.”

As a last example, Hoover Institution professor John Bunzel (a foe of the 1982 amendments) asked in his remarks: “[I]f blacks are mostly Democrats in, say, a predominantly Republican county, is their vote to be considered diluted when a black candidate loses, even when it is agreed by everyone that race had nothing to do with it?” Bunzel opposed Section 2’s revision partly because he believed the answer was yes.

The upshot of all this material is relatively clear. Many of the key participants in the 1982 hearings contemplated a notion much like the SG’s proposal in Callais: that district maps not be deemed dilutive if they diminish minority electoral influence for political instead of racial reasons. But, without exception, these figures thought this notion didn’t apply to the proposed amendments to Section 2. Sen. Hatch, Markman, and Bunzel certainly wished the notion did apply. But they recognized it didn’t by, for instance, critically quoting Days’s and Chambers’s testimony in the Subcommittee on the Constitution’s report recommending the rejection of most of the amendments.

That Subcommittee report was later supplanted by the famous report of the entire Senate Judiciary Committee—the report that gave us the “Senate factors” that have guided Section 2’s interpretation ever since. But if the SG’s proposal in Callais is accepted, it will be as if the Subcommittee report, not the subsequent Committee report, ultimately prevailed. After all, it was the Subcommittee that thought about Section 2 then as the SG does now, and the full Committee—and the full Senate—that rebuffed that position.

Misleading Claims About Affected Districts

Toward the end of his argument in Callais, Hashim Mooppan seemed to assert that neutering Section 2 would affect only about fifteen congressional districts. In his words, “there are only 15 majority-Black districts” nationwide, so the administration’s proposed poison-pill revision of the Gingles framework wouldn’t “lead to there being no Black representation in Congress or anything remotely approaching that.” This statistic, however, is highly misleading. In fact, the administration’s proposal would cause many more than fifteen districts to lose their protection under Section 2.

First off, while there are only 15 majority-Black congressional districts, there are ten more districts with a Black voting-age population above 45%. In the vicinity of most of these districts, a majority-Black district could have been drawn, meaning that the first Gingles precondition would be satisfied — and a Section 2 suit would likely succeed (under current law) — if the existing district was eliminated. Additionally, most of these ten districts easily exceed a 50% combined threshold for minority voters. So if these voters are mutually politically cohesive, and if the relevant circuit is one that (like most) recognizes coalition claims, these districts would mostly be protected coalition districts.

Second, Mooppan didn’t say anything about groups other than Black voters. But there are thirty-eight majority-Hispanic congressional districts (forty over 45% Hispanic VAP), as well as two majority-Asian-American districts (three over 45% Asian-American VAP). Most of these districts are also protected under the current interpretation of Section 2 — either because they’re already majority-minority districts, because a majority-minority district could be drawn in their vicinity, or because they’re coalition districts.

Put all this together and Mooppan was off in his estimate of congressional districts that could be affected by Callais by more than 300%. In reality, there are close to seventy congressional districts that are probably protected by Section 2, at present, and could be stripped of this protection depending on what the Court chooses to do.

The State Interest Solution

I want to return to one possible outcome in Callais—holding that compliance with Section 2 isn’t a compelling state interest—that I’ve previously flagged but hasn’t gotten much attention. Here are some points about this resolution that could be attractive to some Justices:

- It’s a clean way to affirm the ruling below that Louisiana’s Sixth District is an unconstitutional racial gerrymander. Strict scrutiny applies if the district was drawn for a racially predominant reason. Assuming it was so drawn, compliance with Section 2 is the only potential justification for the district. If compliance with Section 2 isn’t a compelling state interest, then the district necessarily fails strict scrutiny and is unlawful.

- It’s a ruling that requires no modification or reversal of any precedent. Over the years, the Court has repeatedly assumed that compliance with Section 2 is a compelling state interest. But the Court has never made any holding to this effect. So stare decisis is no obstacle to this path.

- It’s an approach explicitly endorsed by both the appellees and Louisiana. Per the appellees, “Section 2 compliance alone is never a sufficiently compelling interest” to uphold a district drawn for a racially predominant reason. Per Louisiana, “compliance with Section 2 cannot be a compelling interest.”

- It follows from Justice Kavanaugh’s desire for a temporal limit. For a time, the argument would go, Section 2 compliance was a compelling rationale for racially predominant redistricting. But that time has now passed. In light of current conditions, Section 2 compliance is no longer a weighty enough consideration to greenlight what would otherwise be unlawful racial gerrymandering.

- It would simplify the Court’s racial gerrymandering jurisprudence. In those cases, the operative question would become solely whether a challenged district was drawn for a racially predominant reason. If so, the district would be invalid. There would be no need for a subsequent strict scrutiny analysis (except in the unlikely event that a jurisdiction managed to identify some other compelling interest allegedly advanced by its districting choice).

- It would also simplify the Court’s Section 2 jurisprudence. It would now be clear that Section 2 can never require remedial districts whose design reflects racial predominance. It’s already apparent that, under the first Gingles precondition, plaintiffs must submit race-conscious but not racially-predominant maps. This rule would now extend to remedies as well, permitting them only if they avoid racial predominance.

- It would resolve the case without triggering legal or political earthquakes. Rewriting the Gingles framework for Section 2 claims—let alone striking down Section 2—would have massive implications for the Voting Rights Act, for constitutional law, and for racial and partisan representation across America. Holding that Section 2 compliance is no longer a compelling interest would certainly be a big deal, but it wouldn’t be so seismic a shift.

NYVRA Oral Argument

This is a big week for voting rights oral arguments. Yesterday, before the New York Court of Appeals, I argued on behalf of the plaintiffs in Clarke v. Town of Newburgh, a challenge to the town’s at-large electoral system under the New York Voting Rights Act. The Town argues that the NYVRA violates the Equal Protection Clause, and much of the argument focused on federal constitutional issues. Here are some excerpts from our brief:

Given precedent and practice, this analysis also has only one possible conclusion: considering race to prevent or remedy a breach of an antidiscrimination law is perfectly permissible. In the voting rights context, the U.S. Supreme Court said so just two years ago. “[F]or the last four decades, this Court and the lower federal courts … have authorized race-based redistricting as a remedy for state districting maps that violate § 2 [of the federal VRA].” Milligan, 599 U.S. at 41 (emphasis added). . . .

Past practice confirms that these cases mean what they say. Over the years, hundreds of jurisdictions have taken race-conscious steps to avoid or cure violations of the federal VRA and state VRAs. Countless more public and private entities have considered race to comply with the disparate-impact bans of Title VII, the Fair Housing Act (“FHA”), and New York’s own Human Rights Law. No court has ever suggested that all these “alteration[s] of … race-neutral … system[s]” were unconstitutional. App.-Br. 68. But that is the untenable implication of Appellants’ stance: that the country’s and New York’s civil rights laws have led to unconstitutional conduct on a massive scale for more than half a century. . . .

Under these principles, the NYVRA’s vote-dilution prohibition plainly does not classify by race. It does not set forth one rule for members of one racial group, and another for members of a different racial group. To the contrary, as the Appellate Division noted, “members of all racial groups, including white voters, [may] bring vote dilution claims.” A19. Of course, this part of the statute mentions race-related concepts. But the whole point of Skrmetti is that a mere reference to a suspect classification does not trigger heightened scrutiny. The only basis on which the NYVRA’s vote-dilution prohibition does classify is satisfaction of the statutory elements of liability (racially-polarized voting or impairment under the totality of the circumstances, the existence of a reasonable alternative policy, and the lack of adequate existing representation). Municipalities—not individuals—are sorted into groups based on whether they meet these criteria. This may be a complex statutory classification. But it is not a racial classification.

Destroying Section 2 in Order to Save It

At first glance, the SG’s brief in Callais seems less radical than those of the appellees and of Louisiana. The latter argue that Section 2 is flatly unconstitutional, while the SG’s brief merely recommends modifying the Gingles framework in certain respects. The Gingles framework certainly isn’t sacrosanct, and my amicus brief, for example, also suggests a series of refinements to it. The SG’s brief, however, is a wolf in sheep’s clothing. If adopted, its recommendations would effectively terminate most modern Section 2 racial vote dilution litigation. Its recommendations would also collapse the distinction between racial vote dilution and racial gerrymandering claims.

The main problem with the SG’s brief is its proposal that the first Gingles precondition incorporate jurisdictions’ political goals: in particular, their aims to benefit the line-drawing party and to protect incumbents. Under this proposal, a plaintiff wouldn’t only have to prove that an additional, reasonably-configured, majority-minority district could be drawn. The plaintiff would also have to show that such a district could be drawn without disturbing the map’s existing bias in favor of the line-drawing party and insulation of incumbents. As the SG concedes, this requirement has no basis in the Court’s case law. “[T]his Court has found the first Gingles precondition satisfied without considering partisan effects, even where the plaintiffs’ illustrative map likely would cost the majority party a seat.”

Beyond its novelty, the SG’s proposal is flawed because it focuses on discriminatory intent, not discriminatory results. The rationale for requiring a plaintiff to match a plan’s existing partisan performance is to eliminate partisanship as a possible governmental purpose. If partisanship isn’t the objective of a challenged plan, the logic goes, it’s more likely that the plan is intended to discriminate on racial grounds. But as everyone familiar with Section 2’s history understands, the whole point of the 1982 amendments to Section 2 was to remove discriminatory intent as an element of liability. As Justice Kavanaugh put it in his concurrence in Milligan, “all members of this Court today agree” that “the text of §2 establishes an effects test, not an intent test.” The SG’s proposal therefore defies the Court’s consensus and tries to transform Section 2 into the very thing—an intent test—that Congress didn’t want when it revised the provision.

By turning Section 2 into an intent test, the SG’s proposal would also conflate racial vote dilution with racial gerrymandering. Unlike racial vote dilution, racial gerrymandering is all about intent. A district is a presumptively unconstitutional racial gerrymander if it was created with a racially predominant motive. For this reason, as the SG acknowledges, racial gerrymandering doctrine already includes an effective requirement (technically a strong admonition) that a plaintiff submit an alternative map that matches the challenged plan’s partisan performance. In the racial gerrymandering context, this condition makes (some) sense because it helps to establish race, not politics, as a district’s primary goal. But in the racial vote dilution context, this condition makes no sense at all because discriminatory intent—the mental state arguably revealed by an alternative map—is legally irrelevant.

A final feature of the SG’s proposal is that it would doom most Section 2 claims in areas where most minority voters are Democrats and most white voters are Republicans. In these areas—which notably include much of the South—an additional minority-opportunity district can usually be drawn only at the cost of an existing Republican district. This swap of an old Republican district for a new minority-opportunity district, however, is exactly what the SG’s proposal would prevent.

By the same token, the SG’s proposal would greenlight the demolition of many existing minority-opportunity districts, especially in the South. Suppose the SG’s position were adopted and Louisiana (the home of Callais) decided to get rid of both of its congressional minority-opportunity districts in order to craft an all-Republican map. Any Section 2 plaintiff would then have to prove that a reasonably-configured, majority-minority district could be drawn while preserving the plan’s all-Republican delegation. In all likelihood, this showing couldn’t be made because, under conditions of severely racially polarized voting, any majority-minority district would almost certainly elect a Democrat, not a Republican. Accordingly, the SG’s position would render Section 2 a dead letter in the southern jurisdictions where the provision has historically had its greatest impact. In other words, the SG’s position would set the stage for the greatest reduction in minority representation since the dark days of Redemption in the late nineteenth century.

“Aligning Constitutional Law”

I just posted this paper, written for the Ohio State Law Journal’s symposium on my book, “Aligning Election Law.” The paper explores how the principle of alignment — congruence between governmental outputs and popular preferences — could be incorporated into mainstream constitutional law. Here’s the abstract. I’ll also be giving the Constitution Day Lecture at Drake University today based on the paper.

At present, American constitutional law gives short shrift to the democratic value of alignment (congruence between governmental outputs and popular preferences). But it doesn’t have to be this way. In this symposium contribution, I outline three ways in which constitutional law could incorporate alignment. First, alignment resembles federalism in that it’s a principle implied by the Constitution’s text, structure, and history. So doctrines analogous to those that implement federalism could be crafted to operationalize alignment. Second, comparative constitutional law recognizes democratic malfunctions that involve misalignment as well as innovative judicial remedies for these problems. Likewise, American constitutional law could appreciate the full arrays of misaligning threats and potential judicial responses to them. Lastly, one of the key concepts of modern originalism is the construction zone, in which disputes must be resolved on grounds other than the constitutional text’s original meaning. Alignment could be a factor that courts consider in the construction zone, pushing them to further, not to frustrate, this value.