The following is a guest post from Josh Douglas:

Like Rick, when I was in DC last week I visited the Library of Congress to review the newly-released papers of Justice John Paul Stevens. (Shout-out to the great staff in the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress for being so helpful!) Because the case will be featured in my new book due out in 2024 (tentatively titled The Voters vs. The Court), I was most interested in reviewing the files from Burdick v. Takushi, a 1992 case that makes up the second half of the influential “Anderson-Burdick” balancing test that the Supreme Court uses for “non-severe” infringements on the right to vote. (I had already looked at the case files from Anderson last summer; the newly released papers covers cases from 1984 to 2004.)

Burdick was about Hawaii’s ban on write-in voting. The Court upheld the Hawaii rule on a 6–3 vote. Justice Stevens joined Justice Kennedy’s dissent in the case. That fact by itself is interesting because Justice Stevens wrote the Anderson v. Celebrezze majority opinion in 1983. As the dissent explained in Burdick, “a State that bans write-in voting in some or all elections must justify the burden on individual voters by putting forth the precise interests that are served by the ban. A write-in prohibition should not be presumed valid in the absence of any proffered justification by the State. The standard the Court derives from Anderson v. Celebrezze means at least this.”

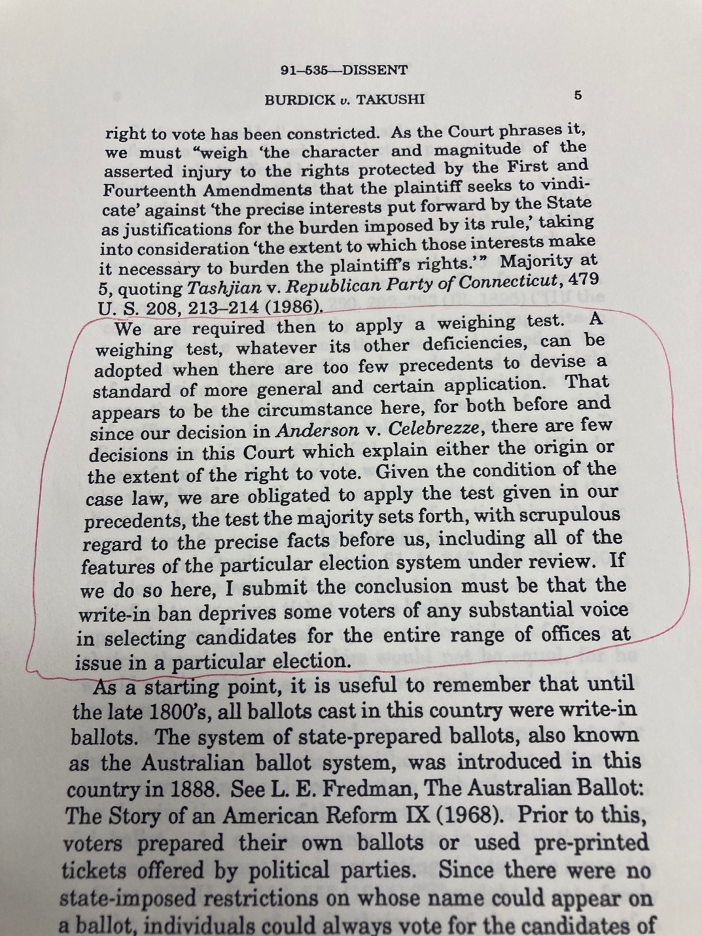

The most interesting tidbit I found in Justice Stevens’s files on the Burdick case was the inclusion of an odd paragraph in a draft of Justice Kennedy’s dissent. Here is the text of the paragraph in question:

We are required then to apply a weighing test. A weighing test, whatever its other deficiencies, can be adopted when there are too few precedents to devise a standard of more general and certain application. That appears to be the circumstance here, for both before and since our decision in Anderson v. Celebrezze, there are few decisions in this Court which explain either the origin or the extent of the right to vote. Given the condition of the case law, we are obligated to apply the test given in our precedents, the test the majority sets forth, with scrupulous regard to the precise facts before us, including all of the features of the particular election system under review. If we do so here, I submit the conclusion must be that the write-in ban deprives some voters of any substantial voice in selecting candidates for the entire range of offices at issue in a particular election.

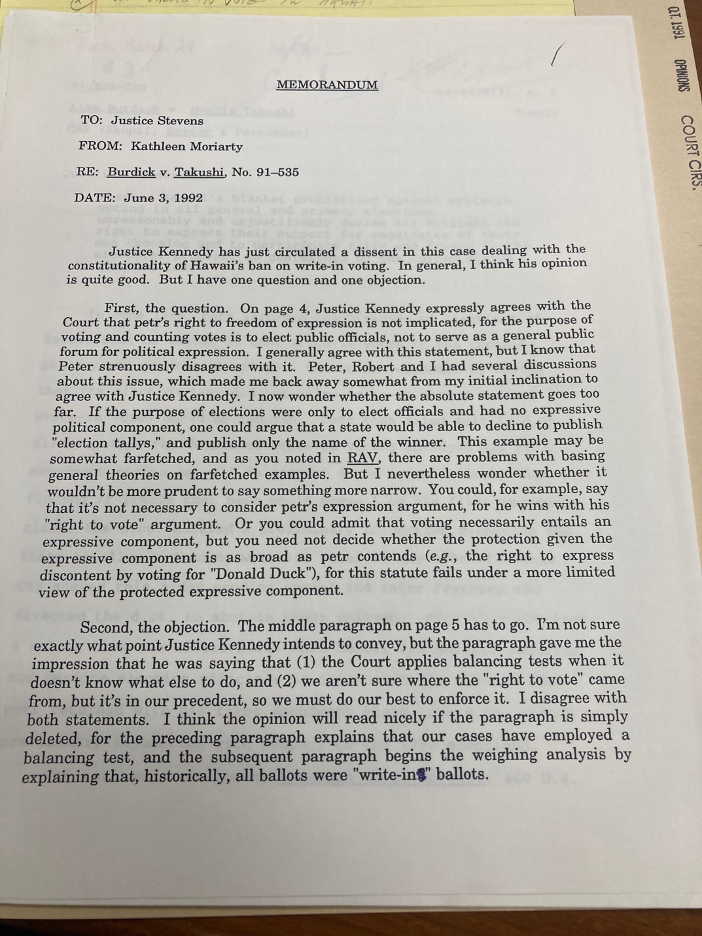

As Justice Stevens’s law clerk pointed out in a memo to Justice Stevens, this paragraph questions both the origins and the strength of the constitutional protection for the right to vote. As the clerk wrote, the paragraph implies that “(1) the Court applies a balancing test when it doesn’t know what else to do and (2) we aren’t sure where the ‘right to vote’ came from, but it’s in our precedent, so we must do our best to enforce it.”

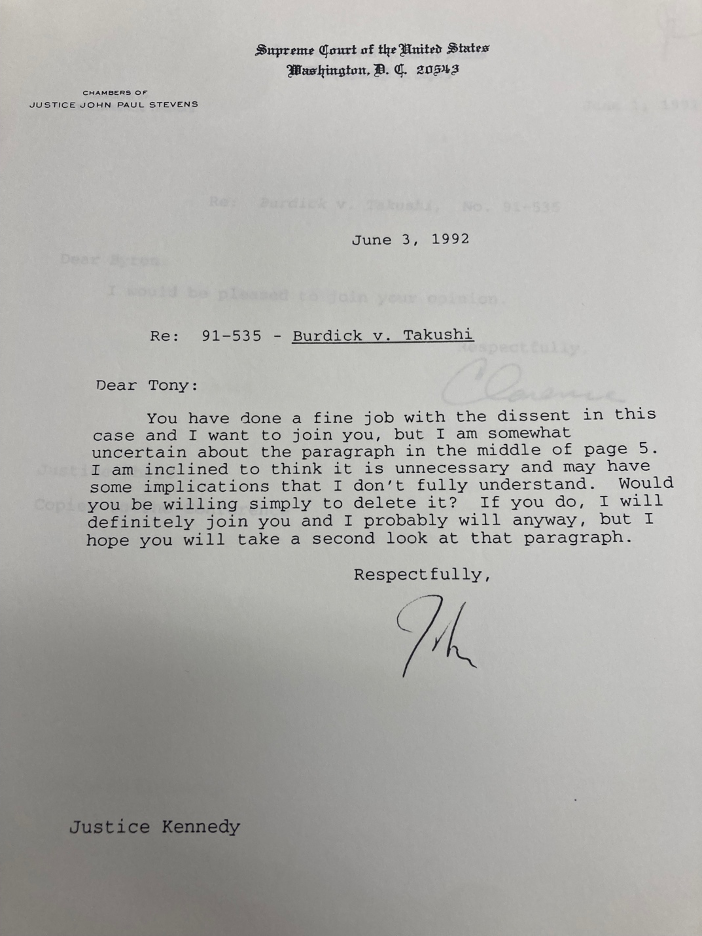

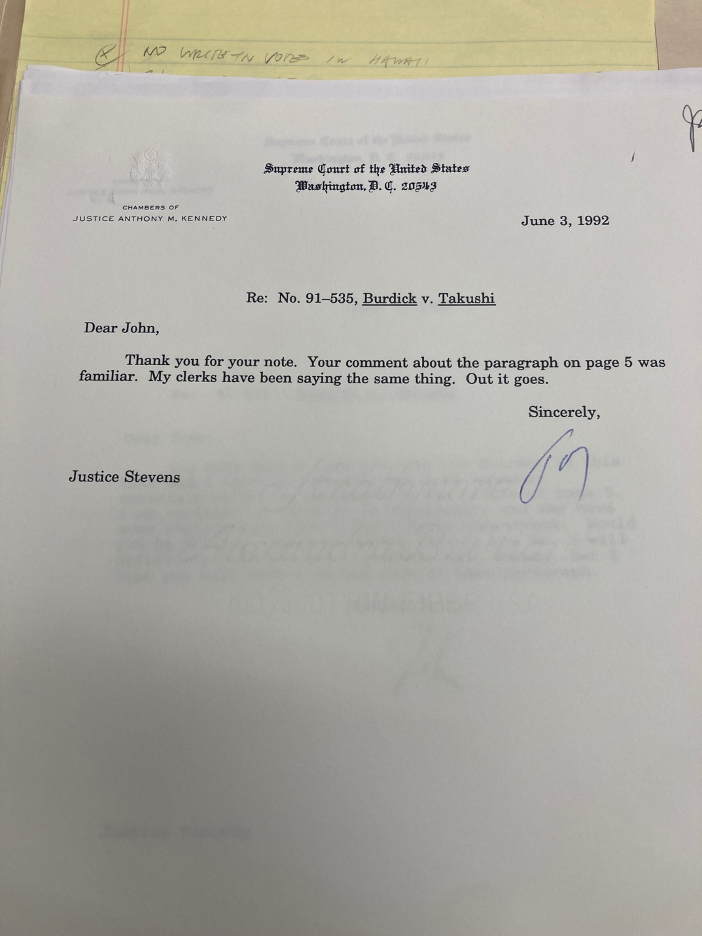

Justice Stevens then wrote to Justice Kennedy to ask him to remove the paragraph, and Justice Kennedy responded that his own law clerks, too, had questioned that paragraph. “Out it goes,” Justice Kennedy agreed.

The final dissent recites the Anderson balancing test and then includes only the last sentence of the paragraph in question: “I submit the conclusion must be that the write-in ban deprives some voters of any substantial voice in selecting candidates for the entire range of offices at issue in a particular election.”

This draft paragraph—especially given that it was in a dissent—is not particularly significant, but it does suggest that Justice Kennedy was perhaps unsure of how to describe the Constitution’s protection for the right to vote. Using the Equal Protection Clause and the Anderson–Burdick balancing test has always been an inartful fit for what should be the most important, foundational right under the U.S. Constitution. As my book will explain, the Court has underprotected the right to vote and has deferred too much to state politicians in election rules—not just recently but during the past five decades. The sentiment in Justice Kennedy’s draft dissent in Burdick epitomizes this view.

Burdick is an interesting case for many reasons. I interviewed Alan Burdick and will include several anecdotes from our conversation in the book. This aspect from Justice Stevens’s papers is not going to make it into the book—it’s a little bit too much inside baseball, I think—but hopefully ELB readers found it as interesting as I did.