The author of this post sends along this follow-up:

This week’s New Yorker profile of Marc Elias was another entry in the ongoing media coverage about the role of the court system in resolving very live disputes concerning voting and the health of our democracy, and the wisdom of the serial seeking of judicial involvement. The New Yorker piece helpfully notes disagreement within the election law community. What it omits or does not get quite right is worth noting.

First, social media has had an adverse effect on general understanding, including in the press, of the actual state of play in the fight over voting rights. Part of that is the ephemeral nature of the medium, which makes the filing of a case appear just as consequential as its resolution. Another part is Elias’s uniquely active social media presence. While his effective use of social media is not without benefit (e.g., rallying an audience to his cause), it also has created a narrative that judicial avenues are likely to reach successful destinations. In the world of Twitter, the average consumer of political news would miss that the sober consensus is precisely the opposite: judicial relief in voting rights cases is increasingly hard to achieve, with skeptical courts, and an evolving and problematic body of law, particularly but not exclusively at the federal level, requiring careful navigation. And the one area of the law that has shown promise—the use of state constitutional provisions to thwart partisan gerrymandering—has drawn the close attention of 4 Supreme Court Justices, who, if joined by one of their two conservative brethren, may not let it last beyond June 2023.

Like most lawyers, athletes, and, for that matter, politicians whose profession depends on future success, Elias is inclined to play up past successes; and to play down past failures. So, we hear from his eponymous Twitter feed about the latest trial court victory; and a bit less about the fate of the appeal. We hear, for example, about an N.D. Fla. decision on Section 2 vindicating last summer’s loss before the Supreme Court in Brnovich. The readers are not warned about the rough waters ahead in the 11th Circuit—or even the trial court judge’s seeming expectation that he will be reversed.

We hear, for example, that the Supreme Court’s April 2020 decision staying orders affecting the Wisconsin primary, RNC v. DNC, — U.S. —, 140 S.Ct. 1205 (2020) was not a harbinger of things to come, but an “endorsement [of] a post-marked by Election Day standard (rather than received by),” sure to “enfranchise thousands of voters in November. Politico, 4.7.20. The Supreme Court had different ideas; presented with the same issue months later, it affirmed the stay of a district court order that otherwise would have extended the mail ballot deadline in Wisconsin for the general election. DNC v. Wisconsin State Legislature, — U.S. —, 141 S.Ct. 28 (2020).

This approach has been consistent throughout the emergence of the Democracy Docket. In 2020, it was especially striking. Prior to the election, Elias and other groups litigated voting access rules around the country, and more than most were lost. Many of the losses occurred on appeal, with the federal courts effectively closed to relief on Purcell grounds beginning in mid-summer (just as RNC v. DNC had indicated they would be). Still others occurred in state courts, like Maine, that on balance might be more solicitous of voting rights arguments than other venues (e.g., Arizona and Georgia) where such cases might be litigated. E.g., Alliance for Retired Americans v. Secretary of State, 240 A.3d 45 (Maine 2020). But on social media, it appeared that the victories were piling up, one after the other, in a crescendo of voting rights successes.

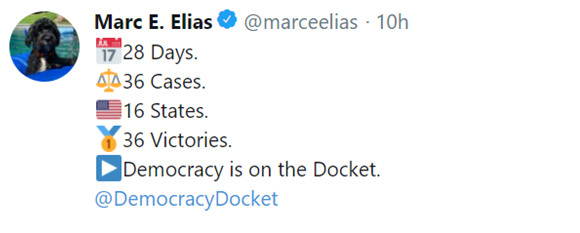

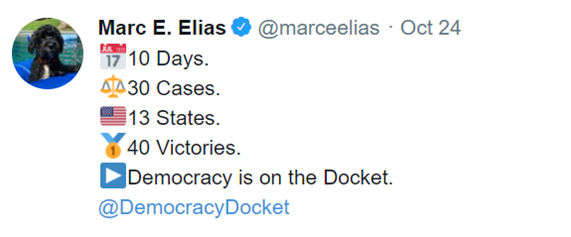

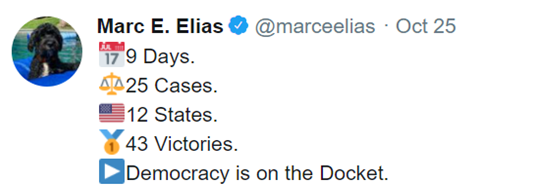

By October 7, 2020, there were purportedly 36 victories; by October 24, 40 victories; and by October 25, 43 victories.

Meanwhile, on the actual docket, whatever victories had been achieved at the lower court level were being stayed or, if rendered in state court, collaterally attacked—not just by more conservative circuits like the 5th (Texas), 7th (Wisconsin), 8th (Minnesota), 11th (Georgia and Florida), but by the 9th Circuit as well (Arizona).

This narrative of success before the courts was carried forward into 2022 in the New Yorker, as it is in other contexts by Elias and others, as evidence that a willingness to fight begets victories; and that an unwillingness to file case after case should be seen as professorial aversion from the fray.

But the record pains a different picture. In the past 18 months, the terrain before the Supreme Court has grown only less favorable, following Brnovich and certain of its actions in redistricting cases over the past several months. In addition, the states with Republican trifectas that are enacting regressive voting laws—most prominently, Arizona, Georgia, Florida, and Texas—have judiciaries at least as unwelcoming to voting rights claims as the Supreme Court.

An effective litigation strategy takes these facts as a given and asks how they can be addressed. With at least a plurality of the Supreme Court willing to entertain claims that state legislatures have some special provenance over federal and presidential elections—separate, apart from, and even in addition to the powers afforded them by their respective state constitutions—how should voting rights advocates comport themselves? With a Court apparently intent on chipping away at the Voting Rights Act, section-by-section and context-by-context, how best can that trend be countered?

These are real strategic questions. While it makes sense in politics to contest every race, it makes substantially less sense in law to file every potential case. And that is all the more true if those cases are filed predominantly to challenge laws in red states.

In evaluating these issues, it is essential to understand the role the courts are willing to play, and to strategize accordingly. All of us who care about the vitality of American democracy are on edge; but litigation is no outlet for our primal scream. If, in Elias’s phrase, democracy is on the docket, then strategy is essential. We must ask whether it has been put there in the manner most likely to succeed and, if not, whether the risk of loss has been calibrated properly. And if democracy is to be on the docket, more consideration must be given to how it gets there, so that the final entry is a judgment in its favor, rather than still more precedent making the next case more difficult.

Moreover, in this setting, declarations that: (1) democracy is on the docket, but (2) democracy protection must be a partisan endeavor of the Democratic party are at odds with one another. Justices appointed by Republican presidents; and jurists appointed by Republican governors (or elected by Republican voters) will be reticent to join such an avowedly partisan cause. The judiciary is not a partisan branch; and, if it were, it would not be a partisan Democratic branch.

The question is less about “saving laws on bookshelves,” than about making sure the next entry in the U.S. Reports, or those of judiciaries in battleground states, advances the health of our democratic enterprise, rather than giving license for its further deterioration. This a critical question that will need to be addressed in the months ahead. And debate over this question will benefit from fewer social media-driven claims and “PR” and more clarity about the experience to date and its implications for litigation strategy.