The Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the Capitol has been digging into the renegade electoral votes submitted by some Republicans in some states that President Joe Biden carried in 2020. POLITICO links to some PDFs of the purported certificates, and FOIAs elsewhere have revealed more. No legislature attempted to send a competing set of electors, and Vice President Mike Pence never introduced them to Congress (nor did anyone in Congress request them). But some Republicans cast votes purporting to support President Donald Trump and Vice President Mike Pence in their states, despite the fact that the Democratic slates of electors were certified as the winners. Those gatherings then sent certificates to Congress.

I’ll get to the lawfulness of even behaving this way in a moment, but there are some significant problems with the certificates apart from that. The Arizona electors met on December 7, not December 14, the date Congress set for prescribed electors to meet. The Michigan electors falsely stated they met “in” the Capitol (which state law requires them to do), when they were excluded from the building.

It’s also telling to see which electors didn’t show. The [son of] late former Senator Johnny Isakson didn’t attend the rogue gathering in Georgia and was replaced. [UPDATE: The Washington Post reports that it is his son, who shares a name.] Neither did former Michigan Secretary of State Terri Lynn Land. The most prominent Republicans, in other words, accepted the certified outcome of the election and didn’t attempt to attend the renegade gatherings.

Is what the electors did illegal? It’s (unfortunately) complicated by Hawaii in 1960.

On the one hand, there are statutes against forgery and general violations of the elections code, as this report in Michigan makes clear.

On the other hand, there’s Hawaii, 1960.

In Hawaii, a very close election gave Richard Nixon Hawaii’s three electoral votes in 1960. He was certified the winner by the governor. But there was a recount, and the recount extended beyond the date the electors were scheduled to meet.

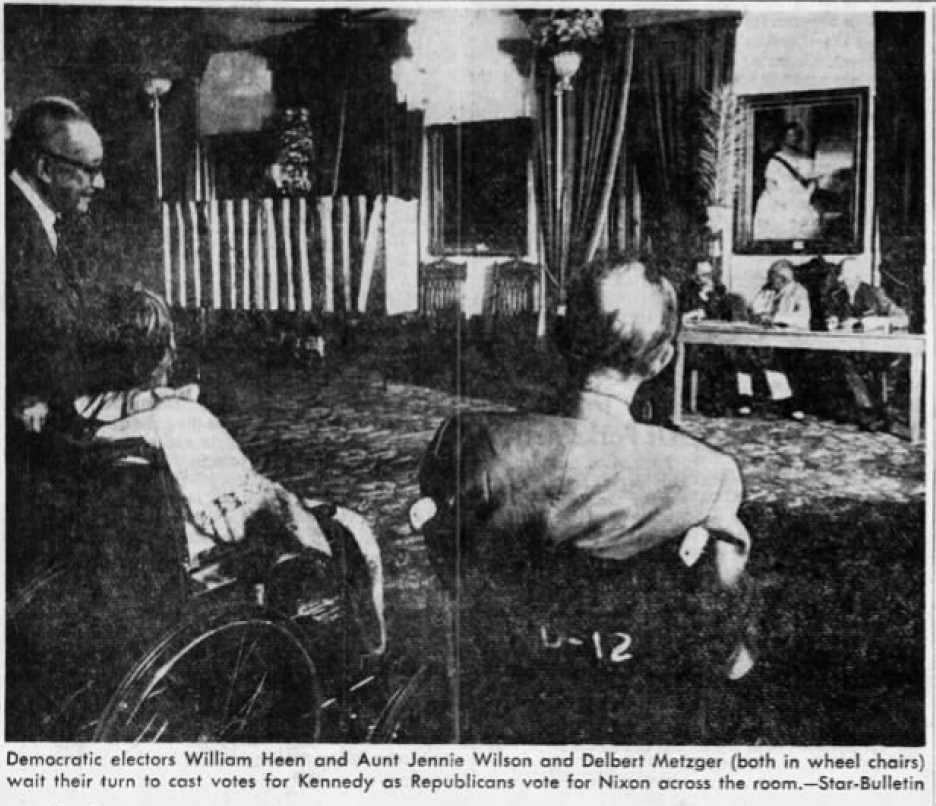

So on December 19, 1960, the three Nixon electors arrived in the Capitol to cast their electoral votes. In the meantime, the three electors for John F. Kennedy literally watched them across the room. The Nixon electors met at 2 pm and wrapped up by 2:45 pm. Then the Kennedy electors gathered at the same table across the room, filled out their own electoral votes and certificates, and mailed them off to Congress, without state sanction.

By the end of the recount in January, a state court concluded that Kennedy, not Nixon, had won the state. As explained by attorneys at the time, the Kennedy electors needed to cast their votes on December 19, even if they had no authority to do so, to preserve their legal challenge in the recount. After all, if they won the recount, they needed to ensure that electoral votes made their way to Congress.

And, in fact, when Congress gathered to count, outgoing Vice President Nixon asked for unanimous consent to count the Kennedy electors over the Nixon electors, which occurred. (He also famously said he was not attempting to set a precedent with this maneuver….) In other words, the electors engaged in a successful gambit, even though they lacked any state authority to act at the time.

Back to 2020. Were presidential electors simply trying to “preserve” their legal challenges in the (extremely) longshot event that they won them? Some legal challenges were pending in some states. They were less serious than the recount in 1960. Should that be the standard, the likelihood of success to determine whether unofficial electors can cast ballots and send them to Congress, even if they have no power to do so? In some states, there were no legal challenges pending (to my knowledge)–should electors in those states face sanctions, as opposed to others where legal challenges were pending? Are there First Amendment implications in asking (petitioning?) Congress to count these votes and not other votes?

Maybe an answer is, Hawaii 1960 was a terrible precedent and should not be emulated–and, in fact, maybe Congress got it outright wrong. If you don’t have a certificate of election, you don’t get to send a certificate to Congress purporting to be an elector.

This, of course, places additional pressure on the certification process and raises additional questions about Congress’s power to adjudicate multiple certificates, including if one lacks the imprimatur of a state official. (One can go back to Reconstruction to see additional disputes on the matter, too.)

In short, I don’t have easy answers about how to square these matters. I know states are investigating how to prosecute these claims. Congress might be investigating, too. Some are much more obvious falsehoods, like purporting to meet in the Capitol when they didn’t. But others look more like “preserving” challenges a la 1960. How much that matters in 2020 remains an open question (as is what lessons it might yield for Electoral Count Act reform before 2024).