I am pleased to welcome to ELB Book Corner Jocelyn Evans and Keith Gaddie, authors of the new book, The U.S. Supreme Court’s Democratic Spaces. Here is the second of four blog posts:

“The basic building block of American governance is the citizen, and the basic unit of American architecture is the citizen’s home.” ~Allan Greenberg, Architecture of Democracy (2006: 32-34).

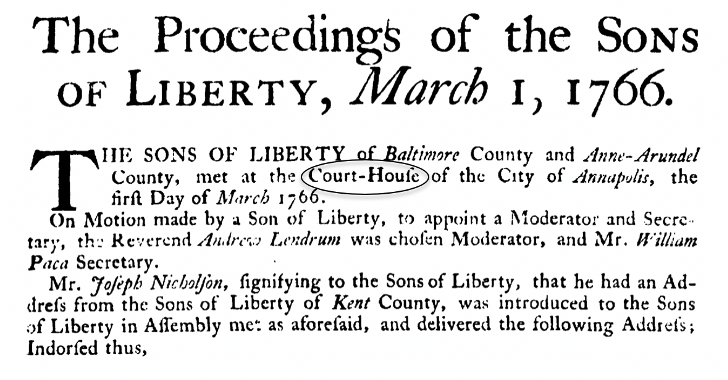

“ Court + House = Courthouse”

When started exploring the homes of the Supreme Court, with the origin of the term and type “courthouse.” The term is not uniquely American, but its widespread use is distinctively so.

“Court” is from the Latin coˉrtem, cohors (“yard,” “enclosure), and courts historically referenced various assemblies, but became associated with judicial proceedings. “House” is Germanic and cognates with Old Saxon and Middle Dutch traditions, referring not both individual dwellings and also other enclosed common spaces. “Courthouse” as a singular English term emerged in the late fifteenth century.

The first Anglo-American civic buildings were meeting-houses imported by Puritans in the early 1600s. These extensions of the home — a communal house — were modeled after domestic architecture. Meeting-houses provided space for both religious and secular gatherings. They stored town records. By the early-18th century, growing religious diversity across the colonies led to meeting-houses being replaced by town-houses. Government business could dominate these spaces set aside from churches to serve secular purposes for the community, including the administration of justice. Markets usually filled the ground level; local governing bodies were on the floor above. Reference to these civic spaces as courthouses became common by the mid-1700s, and the term took hold in the second half of the century.

A pluralism of purpose persisted. Early advertising suggests that courthouses served as fora and meeting places for community events — announcements, electioneering, speeches, scientific demonstrations, sermons, and mobilization of militia. The courthouse type emerged as government grew and the legal profession differentiated itself from other secular activities. The type persists, transactional spaces below, more solemn court space above, and censoring social behaviors to serve as the mainstay of the community.

The separate courthouse structure emerged coincident to the propagation of court systems, institutionalized with the staking of new states, counties, and governments. Governing Institutions — grand juries, ‘courts ordinary,’ ‘fiscal courts’ managed county affairs, and needed permanent seats. County courthouses and county squares logically followed.

Style also changed. As the U.S. broke from Georgian England, this new, multipurpose courthouse shifted from Georgian, and local vernacular styles to the ‘national style’ of Greek Revival or Classical. Later other Neoclassical, Gothic, and various Revival styles took over and became associated with courthouses as a type.

The state and federal courts grew in complexity and permanence. Appellate courts were created. Circuit-riding appellate judges acquired permanent court homes. At the federal level, courthouses, customshouses, and post offices were erected to create both homes and physical presence of the Federal authority.

American county courthouses are today spaces of communal and individual memory. People enter into marriage, adopt children, divorce, bring suit against others, pay fines, face trial, and sit on juries in these spaces. Births and deaths are recorded. They are secular temples for the ritual performance of hyper-localized popular governance, keeping democratic government at the center of everyday life. Whether a result of city planning or grand design, they sit as aspirational reminders of civil society, individual rights and responsibilities, and communal values.

The 1859 Georgian-influenced vernacular White County Courthouse, Cleveland, Georgia (photograph by authors)

The 1902 Classical Revival Colquitt County Courthouse, Moultrie, Georgia (photograph by authors).